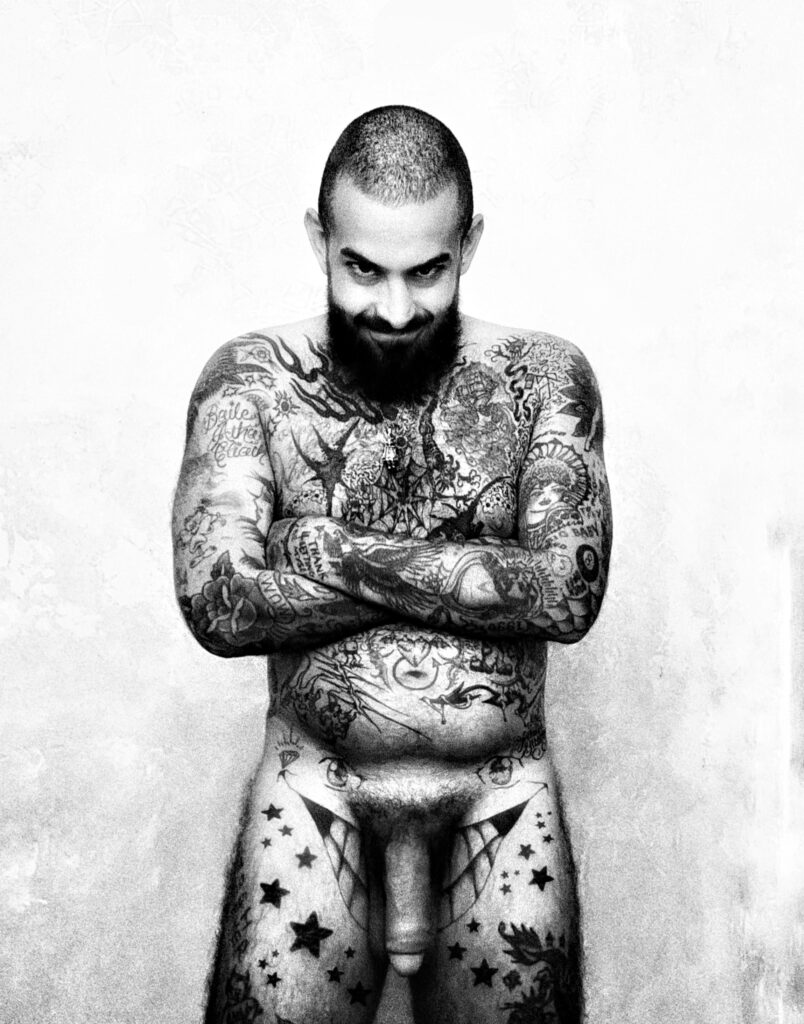

The Transformation of Joshua Gordon

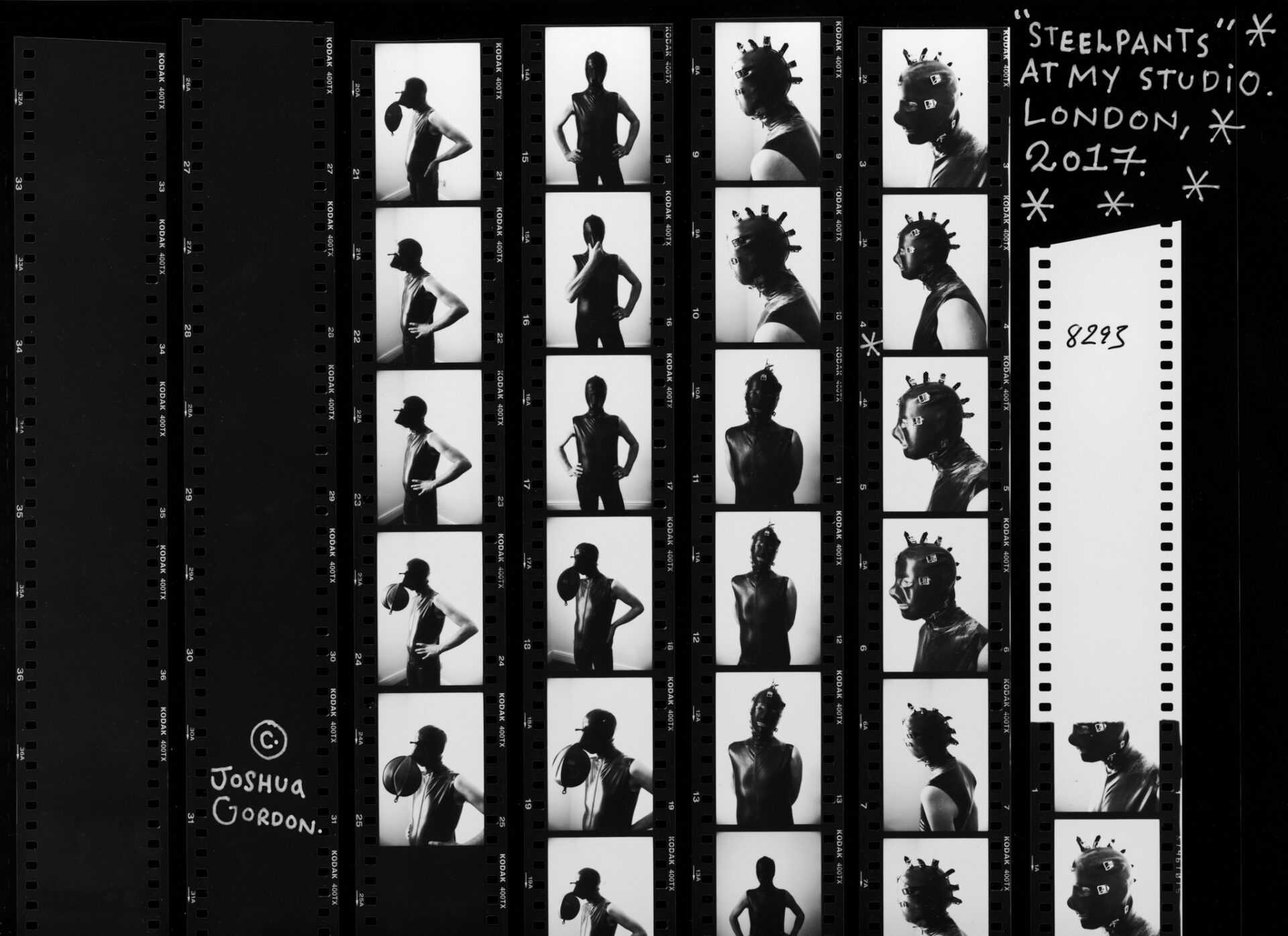

In 2017, in an interview with i-D, Joshua Gordon said that he aims to take “strong photos of unusual individuals.” After producing a series of works in the same year, Gordon’s practise continued to evolve, as did his attitude towards the fashion industry in which he got his big break. “I got so sick of it,” he explains. “I hate working for stupid magazines.”

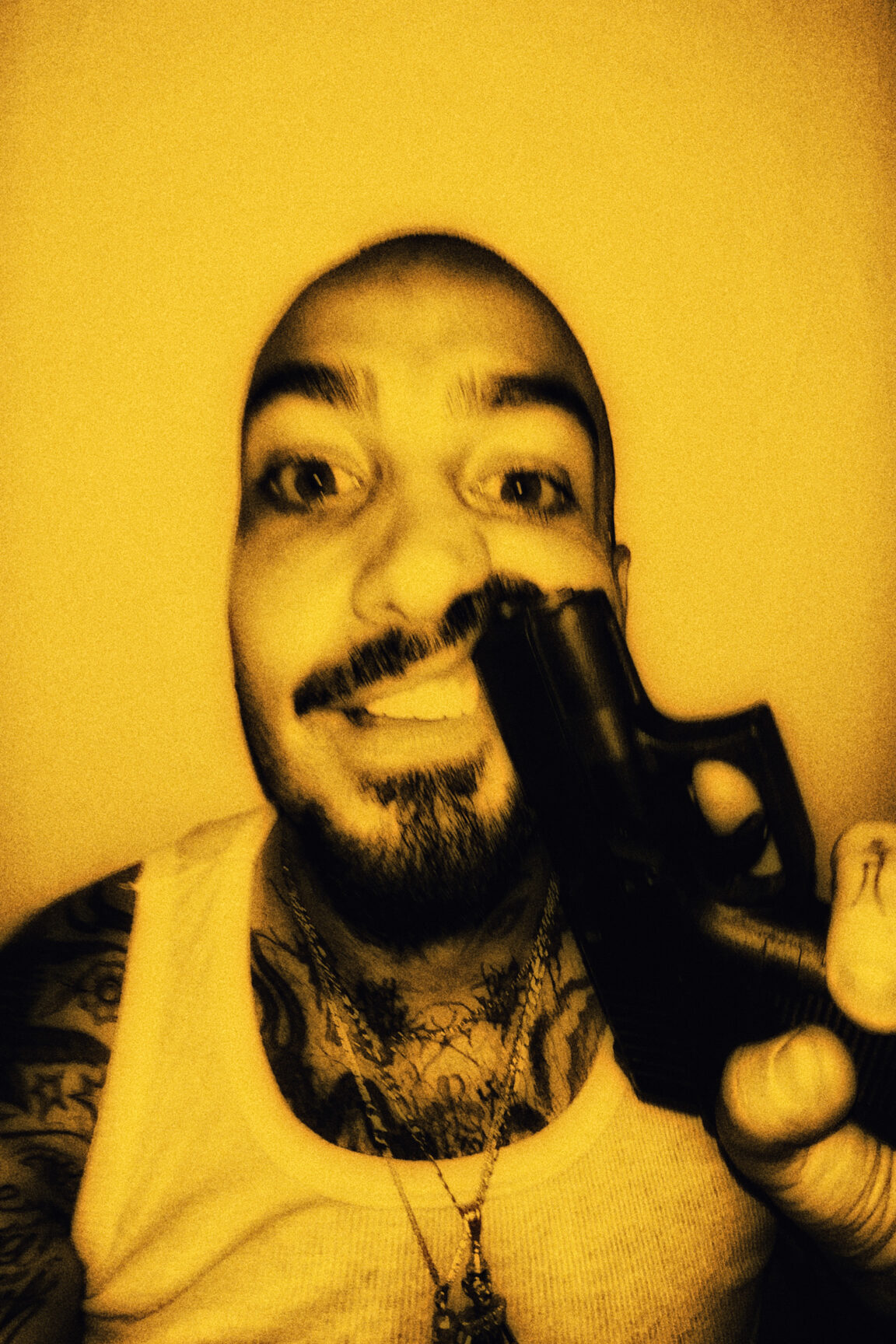

In 2020, Gordon made a swift exit from the fashion industry and found himself on a three-month stint in Mexico, where the makings of his new self-published book, aptly titled Transformation, brewed.

The artist’s appeal, in both life and work, is his honesty. Whether discussing a failed engagement, a relocation or depression, Gordon traipses the ebbs and flows of introspection, explaining his new aim to “transition from making work about other people... to making work about myself.”

Annabel Blue: Hey Joshua, how are you? Are you in London right now?

Joshua Gordon: Yeah, I’m good. Working hard. I just had a solo show coinciding with the release of my new book.

AB: Can you tell us a bit about it?

JG: It’s self-portraits mainly. I can read you the intro if you like?

AB + Sarah Buckley: Yes please.

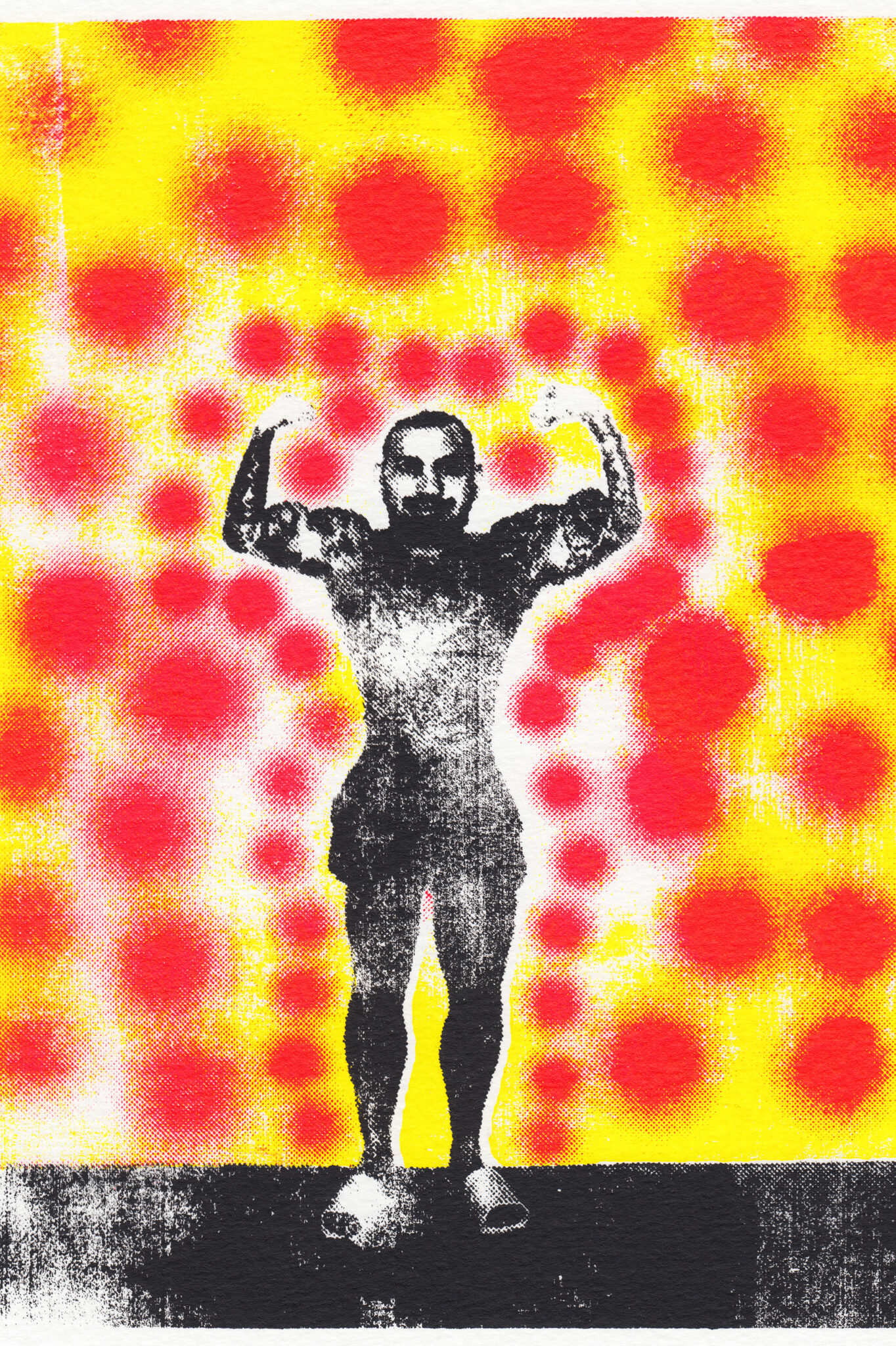

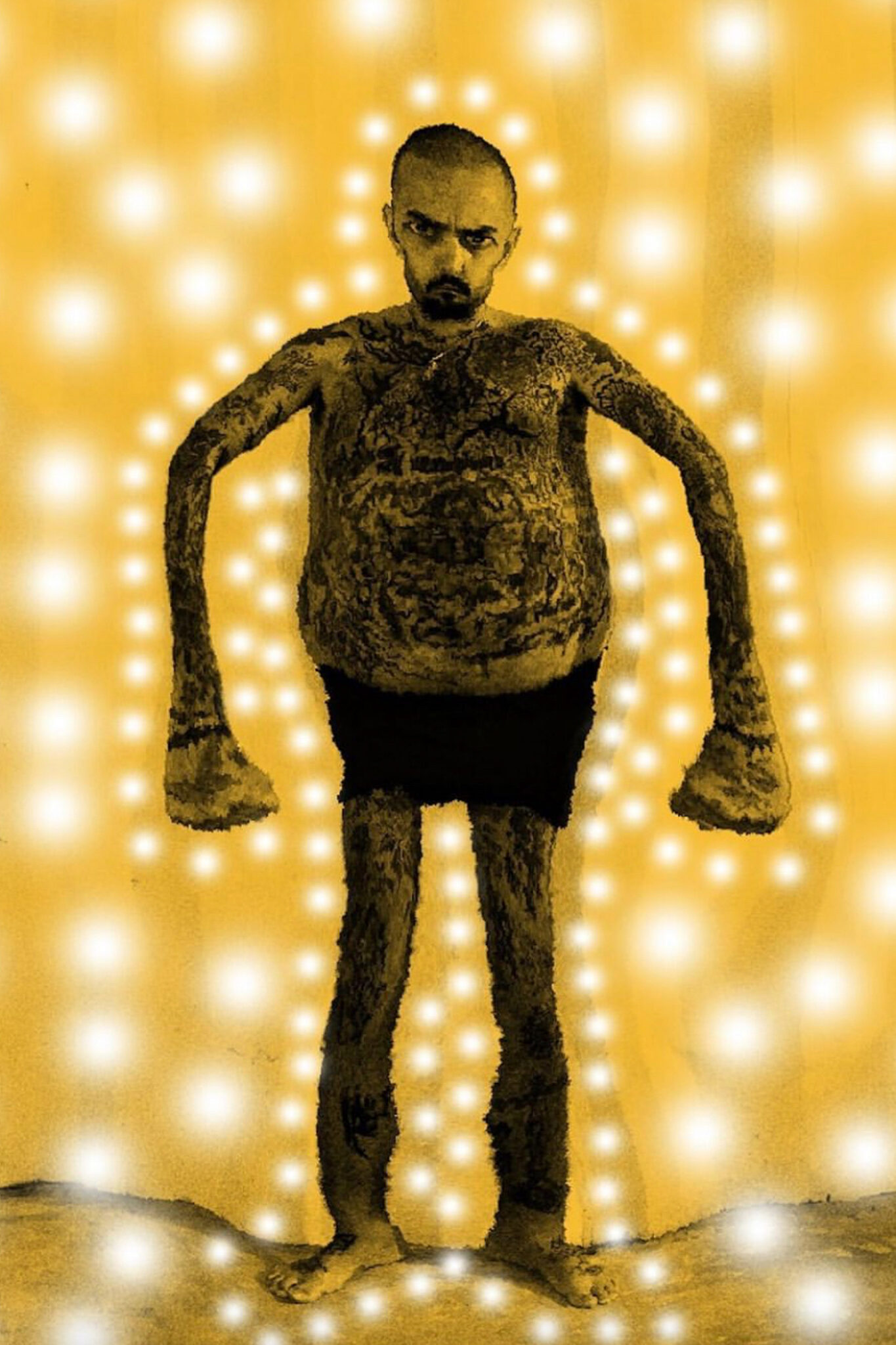

JG: The intro reads: “We all grow, transform and morph into other things. We all change in our lifetimes, consciously or subconsciously. The change is always drastic, whether we choose for it to be or not. We turn from a sperm, to a foetus, to a baby, to some bones and then to dust. Like it or not, change is a must. There is a quote from a Todd Solondz fi lm that I like: ‘People always end up the way they started out. No one ever changes, they think they do, but they don’t. If you’re the depressed type now, that’s the way you always will be. If you’re the mindless-happy type now, that’s the way it’ll be when you grow up. You might lose some weight, your face may clear up, get a body tan, breast enlargement, a sex change, it makes no difference essentially, from in front or behind. Whether you’re 13 or 50, you will always be the same.’ I think about this quote a lot. No matter how much we may change physically, the core remains the same. No matter how I look now, or how I am perceived

by others or myself, I’m still the same ten-year-old weirdo sitting at the back of my classroom wishing I was someone or somewhere else and decided I would live a life, or part of one, on the road. I was jumping from one breakdown to the next, myself and my ex had broken up and I had sold almost everything I owned including my prized super eight cameras, Polaroid film, darkroom, prints and contact sheets. I wanted to leave my old life behind. And I said I would never take another photograph again. I squeezed everything I owned into a single suitcase heading to Mexico. I hid out on the beach for three months with no human contact, spending my days feeding stray cats tuna and listening to the radio. Eventually, I started to make pictures again. But there were no subcultures or subjects I was interested in documenting. Instead, I wanted to make images showing how I felt during this identity crisis. It was my own little daily transformation of sorts, and with my phone and a cheap tripod, I could change myself however I liked and transport myself wherever I wanted to be.”

AB: Incredible. What else comes with it?

JG: You get stickers inspired by the psychic stickers you see in LA on lampposts, a print on thick aluminium and a catalogue of the paintings I did, which were shown in the exhibition.

SB: Wait, so when you left London you headed straight to Mexico? Was Berlin before that?

JG: I’ve been living out of a suitcase for like a year and a half. First I went to Berlin, but I was just partying and doing graffiti and shoplifting ... just being a real nuisance. After Berlin, I went to Paris, then back to London and then left for Mexico. The project was basically shot over three months in Mexico. I didn’t speak to anyone, I was fully isolated and just swam every day, took those pictures and ate seafood.

SB: Who published your book?

JG: It’s my first self-published book.

SB: What else are you doing over the next few months?

JG: Well, I’m gonna do all my boring stuff here then I’m going to go to Dublin to do some music videos. And then I’m going to hopefully move to New York.

AB: So you were working in the porn industry when you were in LA?

JG: Yeah, sort of. I was doing a book about the porn industry.

SB: Were you purely working on it from that aspect? Were you also helping out on set? Or were you just shooting for your own personal work?

JG: No, I was there in a professional capacity. The trade-off was that I had to shoot all

of the digital stuff for them to use on their Twitter and OnlyFans, and if I did that they let me shoot my own stuff. I would also help with lube, applying it to the guys’ hands off camera, and I helped lifting equipment and stuff.

SB: Was it the first time you’ve worked in the porn industry?

JG: Yeah, and it was interesting. They fired me twice because the pictures I was taking for them were so bad! I don’t know how to use a digital camera [laughs]. Then I fell in love with one of the girls who was acting, so she started taking me on her shoots.

AB: Is that where the title of your porn book – I found love in a hopeless place – came from?

JG: Yeah, I thought it’d be kind of funny to name it after the Rihanna song.

SB: What motivated your swift exit from the fashion industry, then?

JG: Well, it was for a few reasons. I just got so sick of working for stupid magazines. I hate Dazed and i-D and The Face, I think they’re total morons. They exploit young photographers and artists to help sell advertising. It’s just business for them, they’re leeches. I just got really jaded with it. I felt like I’d put ten years of my life into photography and I just wasn’t getting much back. I’ve never been able to support myself from photography or anything. So I just said, ‘I quit,’ stopped taking all the commissions and then jetted. I didn’t quit because I wasn’t getting any work. It was more like a cry for help.

AB: You mentioned you had a couple of shoots coming up for brands like Richardson and Bottega Veneta, which I guess are a little different but still fashion.

JG: Yeah, I started getting work again. I don’t particularly enjoy fashion work, but if it can help me pay for my books and stuff then whatever, it’s better than working in a warehouse or stealing women’s handbags, which is what I was doing beforehand … I’m happy to work for Richardson and brands like Bottega though, I love both of them. Dazed will still call and ask me to shoot a fucking Moose Knuckles advertorial, and I’m like … no. I’m doing some drawings for Gucci, which is cool because I like Gucci, but maybe I just won’t do editorials again. Unless they’re for people I really fuck with, or really good magazines like Kaleidoscope, Grind, Re-editon …

AB: Which brings up the question, what do you want to ideally do next?

JG: Well, this past year or two I’ve been trying to transition from making work about other people in other subcultures, to making work about myself and my experiences. Normally I wouldn’t care too much about the porn book, but I think the element of me meeting a girl during the shoot gives it more of a story. I don’t think I want to do traditional documentary photography anymore. I genuinely did quit after Butterfly, but when I got to LA and someone offered the job on a porn set, I thought I’d like to give it a try. But I’m definitely not going to be searching for the next subculture or the next thing to make a book about, because it doesn’t really interest me. It feels like every single thing I’m shooting has been shot better by someone else.

SB: Do you think that your work is dependent on the environment that you’re surrounded by?

JG: Yeah. I’ve never made a project in London or in a place where I’ve lived for a long time. It’s always been somewhere new. When I was in Tokyo, I was so inspired by how different it was that I was taking pictures every day. And the same in Thailand or LA, they feel more cinematic than London or Dublin, the two places I’ve lived for most of my life. I find London to be really boring architecturally. I feel so uninspired and depressed here.

AB: You’re from Dublin originally, right?

JG: Yeah. Dublin is a tiny place with small-minded people, lots of racists and homophobic people. It’s a very old-school place and I didn’t really like living there by the end – I would get called ‘faggot’ and ‘Paki’ every day and I got beaten up because people think I’m Indian. Kids would shout, ‘Thank you come again’ at me when I walked down the street.

It’s draining. I had my nose broken eight times, got death threats, had people calling me from prison. In London, you can just look however you want and no one really bothers you, you know?

SB + AB: Totally.

Joshua Gordon, Girls in car - Shayra, Isabella & Jess, riding to the bar, Cuba.

JG: I find London cringey though. You know, in LA I’ll be hanging out with some sixty-year-old surfer and a weird old rock star and then some porn people. I’m hanging out with people based on their personality, not their clothes. I love collecting clothes. And I love Walter Van Beirendonck, Vivienne Westwood, Bottega … I just don’t really exist within it, you know? I don’t have any friends who wear Walter, I’m friends with people based on their personalities. I don’t fuck with cliques and shit.

AB: What’s the strangest shoot setting you’ve ever found yourself in?

JG: Well, I got signed to this shitty agency like five years ago and they sent me to a refugee camp to make a documentary. They were like, “You can make it on whatever you want and this brand is going to sponsor it and give the money to charity, blah blah blah.” So I went and there was this billionaire guy who ran the brand and he had an entourage of blacked out vehicles with armed security. He was really weird – manipulative and crazy. His name is Roy Luwolt, and the brand was called Malone Souliers. So my cameraman and I get in the car to go to the refugee camp and the armed security are like, “Don’t look them in the eyes, they’re going to try and kill you.” But we get to the camps and meet these mega friendly, curious young Afghani guys, everyone was cool. And then Roy was like, “We’re gonna take photos of all the refugees in high heels.” And we’re like, “What the fuck? They want us to do a look book in a refugee camp with refugees …?”

SB: Holy fuck.

JG: Then we took that Roy guy to court because we basically lost like $10k on expenses like paying for the shoot, renting the camera. He’s in prison now for embezzling half a million dollars of the company’s money.

AB: Wow.

SB: That sounds diabolical.

Michella Bredahl's latest book Love Me Again

By Georgia Puiatti

Sakevi Yokoyama’s Oppressive liberation spirit Volume 1

By T.

Holla, CHAD MOORE! The big apple’s sweetheart

By Annabel Blue & Sarah Buckley

Ed Templeton: Time Flies When You’re Kissing and Smoking

By Annabel Blue & Sarah Buckley

The Unfettered, Sex and Drug-fuelled Youth of New York City by Alain Levitt

By Guest

What To Know About PHOTO 2022 This Year

By To Be Team