THE DEATH of EGO

The Death of Ego: James Robinson on Leadership and Abuse in the Creative Industry

By James Robinson

For generations of people in creative industries, the implication has always been clear: the artist is in charge.

In most ways, this is entirely true. A piece of art, while it is being created anyway, belongs to the artist. The artist invokes a sense of divinity in the creation of work, channelling a vision or emotion in the mind and body, and becoming a vessel to realise this into a material form that audiences can engage with. It is, before all, a personal expression that requires deep internalisation and self reflection.

However, while this is healthy and practical for creative mediums that only require one creator – a painter, an author – as we start to expand into practices that rely on the collaboration between teams, how do power and hierarchy leak into collaborative dynamics? What purpose does it serve? And more pressingly, how can we begin to unravel the behaviours passed down from the less inclusive generation of artists ahead of us?

For these mediums, the photographer, the director, the artist, is the leader. Without someone to guide creative decision-making between so many people working together, cohesiveness and intent are sacrificed. Only, this is where things aren’t so universally defined. A ‘leader’ looks different to many people. To some, to lead is to take control. To others, a leader doesn’t assert power, but deconstructsit.

It’s in these murky waters of leadership that abusive set practices fester.

When I first moved to New York City in 2017 at the tender age of 21, I worked on many sets in a more removed sense: as a behind-the-scenes video artist, a set photographer, or a lighting designer. It meant I had access to the world of the upper fashion echelon, working alongside some of the world’s most successful photographers and stylists.

My practice was born out of joy. Working with friends most of the time in Melbourne before I moved, photography and video work was always fun and grounded: a collaborative environment where every opinion was respected and consent regularly checked. Only, here in New York, the people I worked alongside were having panic attacks, crying, yelling; in one case, throwing a poké bowl across the room. I wondered how something I had always found so fun could rouse so much anxiety and tension. And then I had my first insult thrown my way for angling a light a few degrees off. My co-workers weren’t crying because the stakes were high or they made a mistake, but because the creatives running these sets were exercising their power at every turn.

What is this power? And whose power is it?

These sets weren’t places where leaders were listening to those they were leading, they were ones where collaborators were silenced, and sometimes, humiliated. Assisting the egotistic artist is like climbing rungs on the ladder of success, only to find they’ve kicked out the rest of the rungs above you before you got there. The egotistic artist doesn’t care about your success or wellbeing, only about theirs.

It was a sobering progression of my career to find myself on these sets, although not entirely a surprise. I had always hoped The Devil Wears Prada was dramatised, that the world of fashion and publishing was actually much more welcoming and kind. But New York is a long way from Australia, and the reality set in relatively quickly. From stories of photographers like Terry Richardson or directors like Terry Gilliam (just recently called out by actress/director Sarah Polley, who was intentionally misdirected to run through a field of explosions to capture ‘authentic fear’ as a young girl in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) – this was just how the industry worked. You want to create a masterpiece? You better make sure everyone knows who’s boss.

While I was lucky to mostly escape the yelling and finger-pointing myself (a perk of my fly-on-the-wall video approach), friends haven’t been so lucky.

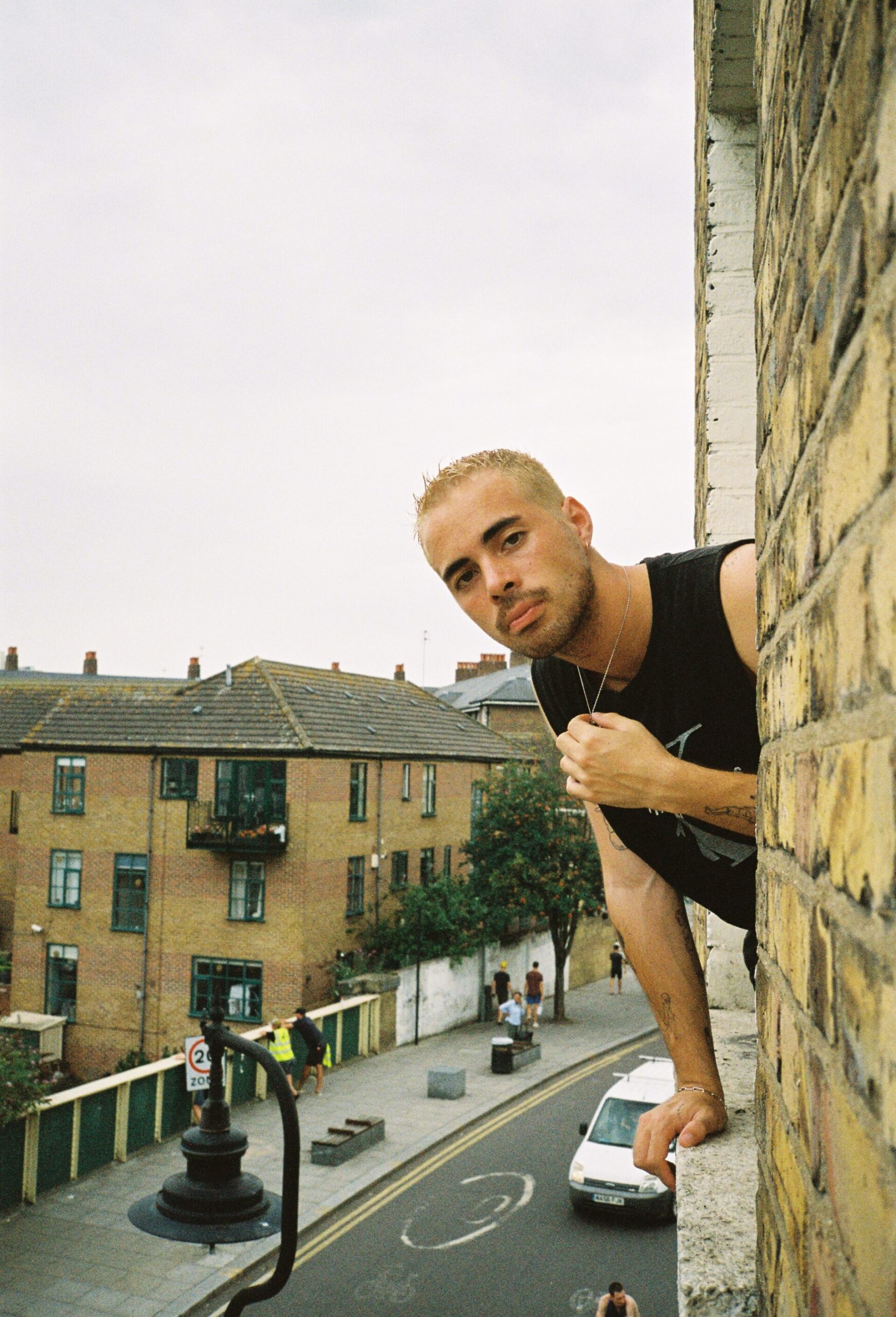

James Robinson Shot By Joseph Haddad Photographing Rose McGowan

Dani (whose name I have redacted at her request), a photographer in Australia, recounted to me an experience she had assisting a celebrated photographer over fashion week a few years ago. Unsurprisingly, there was no compensation or meals, despite 19 hour work days. For assistants, unpaid work is part of the industry pathway. This is where classism and privilege come in. Can’t afford to work for free? That pathway gets mighty narrow.

In Dani’s case, she was exporting some images for this photographer in a room with other journalists and members of the press, and after accidentally misnaming the files, ‘he bent down to me, maybe an inch from my ear, and screamed – “What the fuck is wrong with you! You’ve fucked it all up!”’

‘I went to the bathroom and cried my eyes out. Just thinking about it makes me shake,’ Dani tells me. What’s most frightening to both her and I isn’t only the abuse, but the silence from journalists and photographers that saw it.

How normalised is the artist hubris that this behaviour doesn’t stand out? The press room silence is loud, as if to say with a tired shrug, ‘this is how the industry works.’

Yes, it is the photographer’s power that allows behaviour like this to exist unchecked in professional settings, but it’s also industry complacency too. Dani tells me, ‘Since then, I’ve experienced being screamed at on set, been physically pushed and pulled, had my money withheld… [even] been called names by a producer.’ Recounting these experiences, the real tragedy comes into focus: ‘I love photography and I love film, but half the reason I’m in and out and not committed is the treatment I’ve faced.’

The mentee/mentor relationship is meant to be centred around guidance and support. The hope is that through working together, you can help someone achieve their full creative potential. You can help them navigate an inaccessible industry, teach them about the mistakes you made, and encourage them through gruelling self-doubt and imposter syndrome.

Yet from the friends and creatives I’ve spoken with, the majority say assisting another artist eroded their own enthusiasm. It brings forward a nauseating question: how does abuse inhibit the natural succession of creative generations? How many creative geniuses have we lost to the egomaniacal artist?

These questions also rang true for Art Hoe Collective’s curator, Jheyda McGarrell, who worked for a ‘very famous’ photographer in the USA. They tell me that ‘not once [were they] paid or given an assistant credit.’ While this story is sadly much too common to rouse much sympathy, they went on to explain that they ‘weren’t allowed to speak to talent, even if [they were] spoken to.’

When do unhealthy collaborative practices progress from enforcing power dynamics to actually being dehumanising? Policing unnecessary rules like these is a great abuse of power, and we can’t unpack power without acknowledging how systems uphold hierarchy.

In Jheyda’s case, they discovered their male co-workers (also working as assistants) were being paid. In Dani’s case, she recounts, ‘As a woman there’s already a set of principles I have to deal with before I even step on to a set.’

Systems of oppression bleed. Minority groups are disproportionately affected by these behaviours; especially given older generations exist in bubbles of privilege that emerging ones do not. Yet while we acknowledge these dynamics plague creative industries, let’s acknowledge something else too – the older generations of creatives who enforce them don’t necessarily control the industry anymore.

Violence and power aren’t individualistic. They create patterns. Without self-reflection, this kind of trauma bleeds into the psyche, and often victims of abusive artists like these eventually go on to have their own careers where they exhibit the same behaviour. And why wouldn’t they? That’s the way they were taught the industry operates. That’s the way your vision comes through completely, and how a masterpiece is created. The comfort and safety of people on your set comes after the creation of a work. Right?

Well, not so much these days. Jump forward a couple decades and now we live on the precipice of the end of a creative generation. Since Tumblr and Instagram made art and inspiration accessible to everyone, successful artists are younger and in bigger numbers than ever. No longer do we need to jump through the hoops of agents and galleries to secure and exhibit work, we can do it ourselves. And this sets a new precedent: a generation of people who are lucid to systems and boundaries are taking control of the industry.

Speaking to a New York editor at Refinery29 I’ve worked with for many years, she’s witnessed first hand the shift from established photographers to emerging ones. She thought of a photographer she commissioned recently, who she was only allowed to communicate with through their assistants: ’Why would we put up with photographers who don’t let us speak to them directly when we could hire a younger photographer who’s actually excited to be there?’

This question signals the shift we’re witnessing – in the post-celebrity world of social media, a saturated sea of creatives and influencers, how much currency does a lifetime of celebrated work really hold? Is it enough to make people put up with abusive behaviour? Not really, it seems. And to take it even further, does the insecurity that’s left in the wake of usurped power contribute to the way these creatives treat those working for them?

As my Refinery29 editor says, ‘The old guard knows the industry has changed. Where they were once miles in front, they’re now behind. For some, they keep up with the standards, for others, they react by trying to bend the industry back to how it once was, through entrenching a hierarchy with yelling and abuse.’

For all its cons, being a creative in the Instagram era is also truly humbling. You could be the best artist in the world and still find a hundred people doing something similar to you. And while this does sow self-doubt, it deconstructs our ego too; and ego is at the heart of abusive collaborative practice. If you think you’re better than everyone else, then that means everyone else is below you, even those you need to collaborate with to realise your work.

Musician Phil Elverum in his track Distortion recounts the experience of watching a documentary about American literary hero Jack Kerouac. In the documentary they interview his daughter, Jan Kerouac, who tells the story of an absent, drunk father ignoring his familial responsibilities. Where does the hero end and true self begin? Elverum no longer saw the hero in Jack Kerouac, but a man taking “cowardly refuge in his self-mythology.”

I think those words capture something incredibly specific to the image of the successful artist, who gets away with bad behaviour by hiding in the shadow of their respected public persona. With ego taken away, there’s nowhere left to hide.

With the changing of the tide comes a wave of artists whose work isn’t born out of power tripping in collaborative spaces. Instead of hinging on hierarchy to produce good work, younger artists are more invested in the power of a safe space, where the priority lies in the wellbeing of the team over the outcome of the artwork.

For photographer Jess Brohier, steps she takes to make her sets safe include checking everyone is comfortable (talent and crew) at regular intervals, as well as enforcing breaks and letting people know she’s there to discuss anything that’s going wrong. Creating a safe space for everyone guarantees true collaboration. With the minds of so many people coming together, there is a missed opportunity when an assistant is silenced. They might have ways to make your work better, seeing things from an alternative perspective that isn’t so ingrained by an entire career.

Gabrielle Pearson, head of production company Majella, shares a code of conduct document with every collaborator on her set: outlining behavioural standards every crew member, regardless of title, must adhere to. She also provides names of multiple staff to report incidents to, and even outlines the manner in which to receive behavioural feedback without getting defensive.

For myself, one way I’ve been trying to deconstruct dynamics is by cooking homemade meals for everyone on set, encouraging us all to share food before we shoot (talent alongside the assistants and all), so we can interact in a setting where everyone is equal. By doing something for everyone on set, I assert my place as someone who is in service to my collaborators, not the other way around.

To have someone assist you doesn’t give you power in a dynamic, it gives you a responsibility of care. For many assistants, you’re giving them a glimpse into an industry they hope to be in themselves one day. So the question is, what kind of industry do you want them to be building?

My practice was born out of humble collaboration with friends, then thrust abruptly into an unhealthy industry of hierarchy halfway across the world. Ever since, I’ve been trying to find any possible way to bring myself back to where I started; how can I bring the relaxed, candid energy from those days to even the most high-pressure jobs?

As we slowly drift away from the era of power abuse and artist ego, I can see a creative industry that operates on support, empowerment and access. The power is in our hands to finally stop the patterns of abuse that the older generation are passing down to us.

Is the perfection of your work coming at the expense of the wellbeing of your collaborators?

If art can heal, why use it to damage.

Phoebe Philo launches her long-awaited namesake fashion brand

By Sara Hesikova

Simple, Sparkly, Striking Sandy Liang!

By Rachel Weinberg

Chapter Two of the Love Affair with Gucci and The North Face, with the Environment in Mind

By To Be Team

In between New York and the French Alps

By Anna Prudhomme

Be My Beau

By Molly May Taylor

Ye Does His Craziest Thing Yet: Yeezy Gap Engineered by Balenciaga

By Rachel Weinberg