Picture Me Rollin’ – The Photographs of Estevan Oriol

Picture Me Rollin’ – The Photographs of Estevan Oriol

Words by Mahmood Fazal

Photography Estevan Oriol

Estevan Oriol’s work may be known around the world, but his practice can be traced back to his hometown of LA and his family – his father is also a renowned photographer. “Back in the day, everybody just had little point-and-shoot cameras. My early cameras were like a Yashica T4,” remembers Estevan. “I had this little panoramic point shoot, and then I had a Polaroid camera. But I didn’t get into photography until my dad bought a real 35mm camera. It was a Minolta SRT2.”

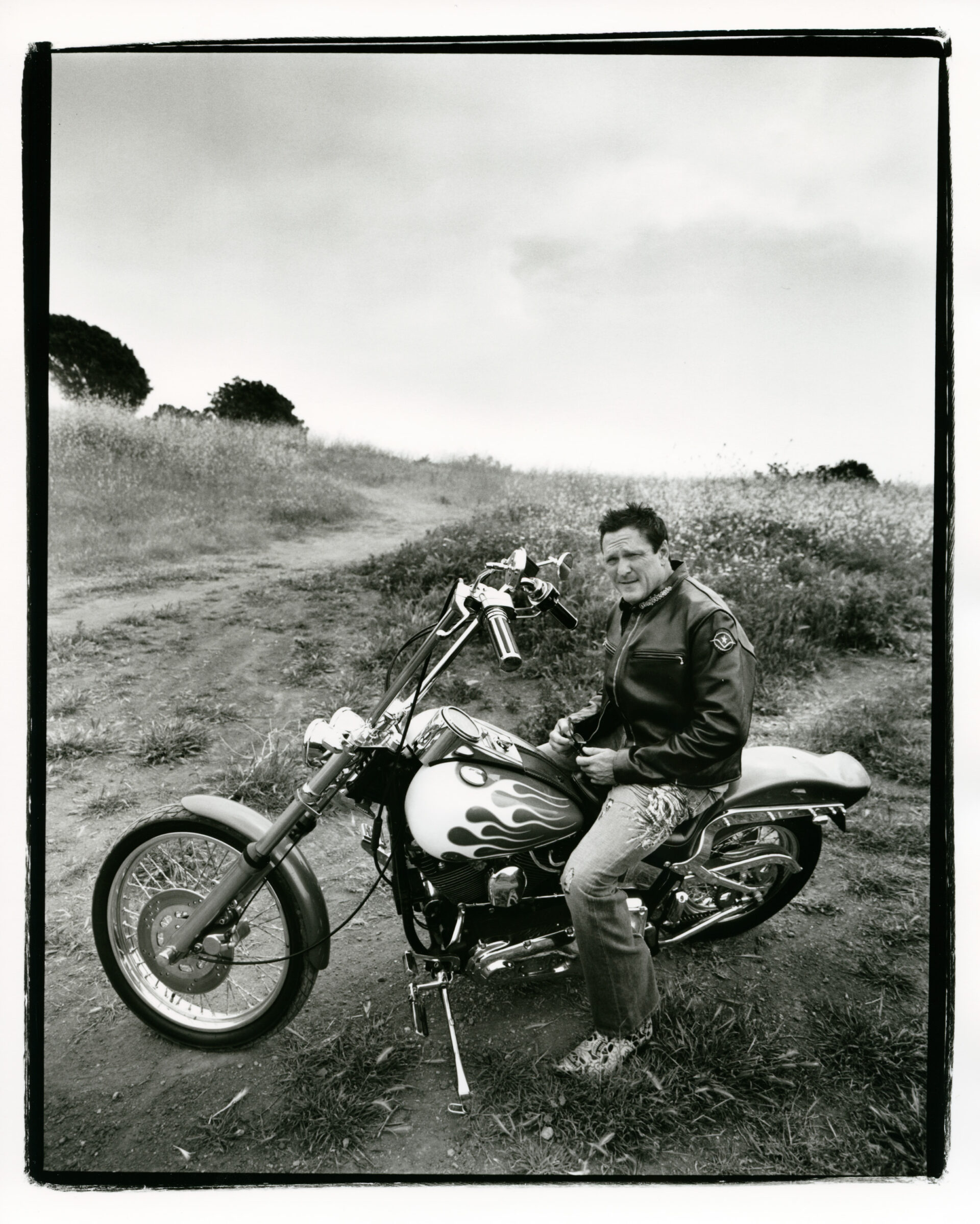

For Estevan, the LA he played a part in was larger than life, and his images are textured by the atmosphere of the scene and the personality of the figures. “Rough, rugged and raw,” quips Estevan. “I was lowriding before I got into photography and I was already tour managing House of Pain. So my first pictures were being on tour with House of Pain and of my lowrider friends.”

Although there were photographers conducting studio shoots of lowriders for magazines when he started, there were no documentary shoots that fleshed out the Chicano subculture from the inside.

Lowrider culture can be traced back to Los Angeles in the 1940s, where Mexican Americans would roll around the city “low and slow.” Nowadays, candy-paint Imapalas with velvet upholstery and gold spoke rims are fitted with hydraulics to bounce around LA illegally. Estevan’s journey began in these car clubs. “I had a 64 Impala SS,” he tells me.

He goes on to explain: “Car clubs have chapters in different cities. We felt like our car club was the number one car club in the world, so we’re like, ‘We’re not going to have chapters in other cities that we can’t regulate to make sure they’re doing the right thing and acting right.’ So we only kept it in one city, in East LA. If you wanted to be in our car club, you had to be in East LA or come to East LA.

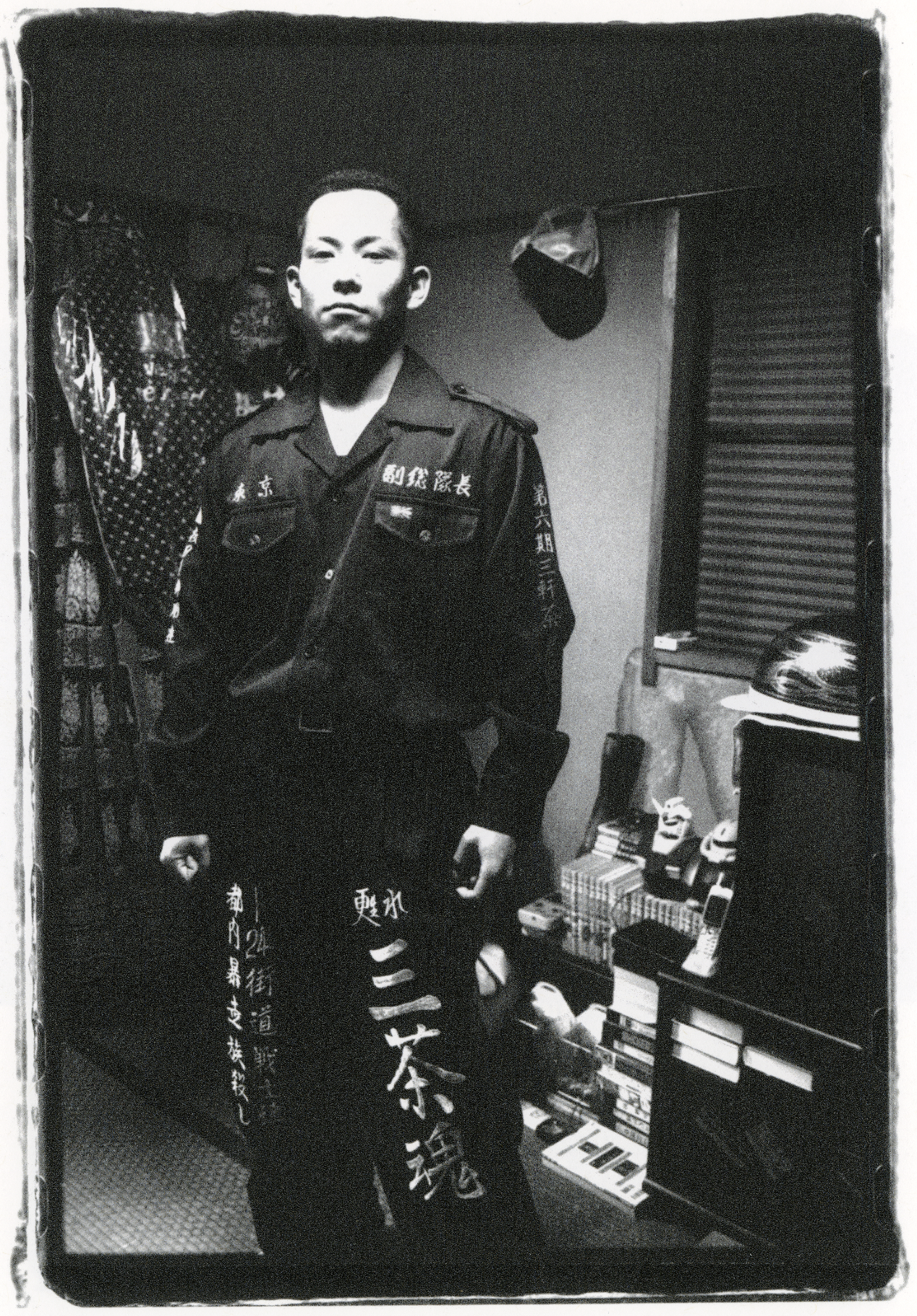

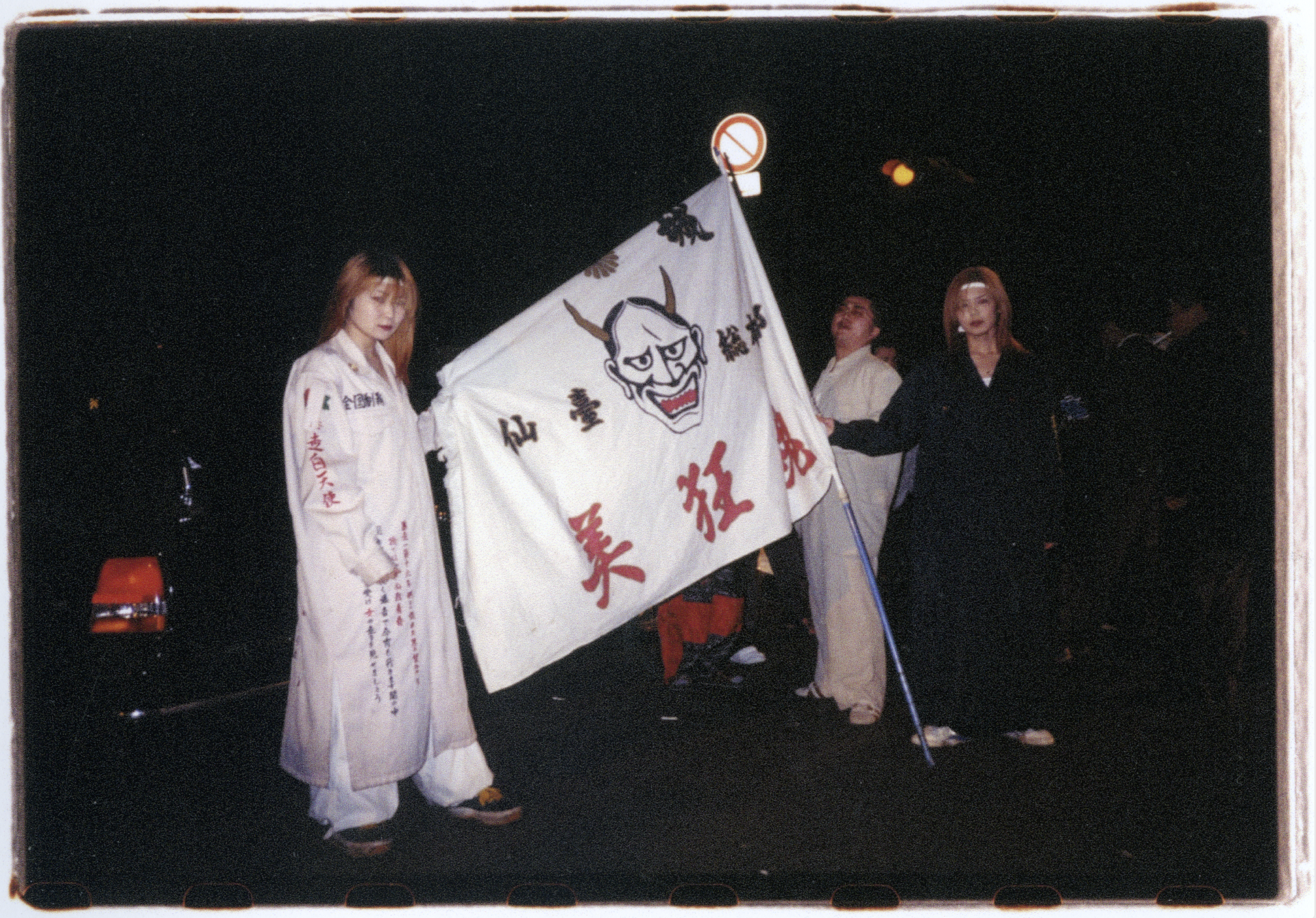

“We had a friend, Oishi, who was from Japan. He wanted to be in our car club, you know, really bad. So he ended up moving his family from Japan to East LA to join our car club. He was friends with a guy who ran a magazine in Japan called Fine Magazine, which was a culture magazine, and he wanted some lowriding photography. Oishi wasn’t into photography; he just wanted to build cars. So I started sending them pictures.”

Estevan would take the photographs and legendary artist Mister Cartoon would add the graphics. Together they captured LA counterculture and gave shape to the LA streets, mashing together tattoo culture, lowriders and hip hop. In one of his most iconic photographs, a girl with gold rings and long manicured nails throws the LA hand sign.

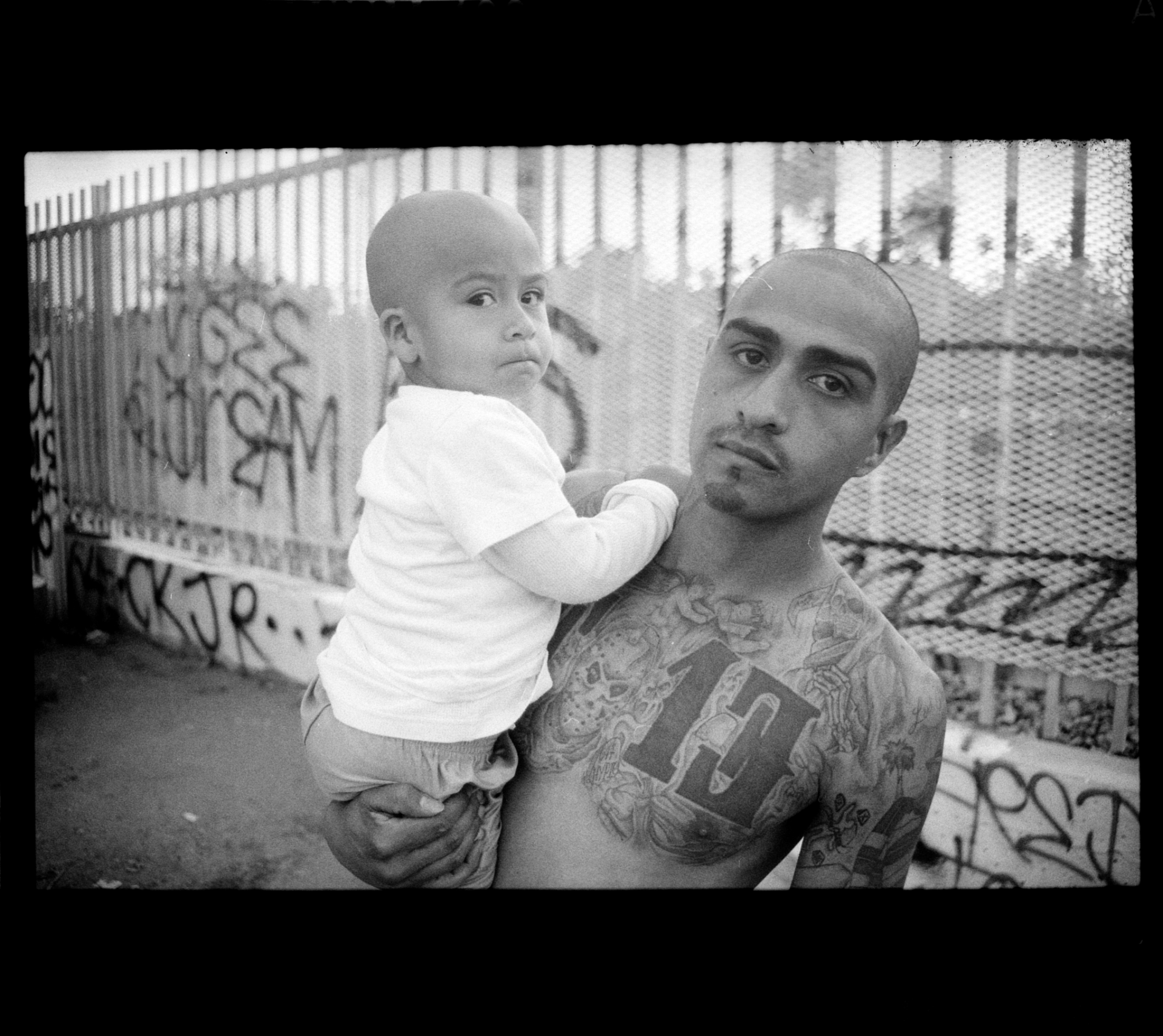

“I was just taking photos of what I was around on a daily basis, which was low riding and hip hop. There was so much I missed because I was in the culture – I was living it,” says Estevan. “I had a car before I had a camera. I see people from like Switzerland, Sweden, Germany, or wherever, come here with the intention of wanting to shoot gang members in LA. If I wasn’t part of it, I would have the craziest and biggest collection of low rider and gangster photos. But I was part of it. I wasn’t always out there with my camera like that. That was secondary; being in the moment was first.”

Sometimes being in the moment cost Estevan the opportunity to capture some of his most cherished memories. An afternoon with his favourite boxer, the world champion Johnny Tapia, still haunts him.

“So I got what I needed. One roll. I’m good. And then he was like, ‘So we’re done? Okay, fuck it, let’s go eat.’ We kicked it for like two hours eating and him telling me stories about having a shootout with the feds. Him and his brother were in a standoff. I look back on it now because he died. And I was like, ‘What a fucking asshole.’ Like, I was a big fan of his when I shot him. Why didn’t I just shoot like 10 rolls of him?”

The portrait that Estevan took of an aging Johnny Tapia, with a shaved head and ‘mi vida loca’ scribed across his belly, is a monumental image of a suffering warrior. With his back to the punching bag, he is making amends in the gym where the journey began for him.

“Now 10, 20 years later, I’m like, ‘Fuck! I should have taken more rolls. I should have shot all these gangsters.’ And now I could put it out and they wouldn’t care, or they’re dead or in prison,” says Estevan. “There were times that I hung out with Eazy-E but I wanted to be respectful and I’m thinking that one day I’ll have a job shooting him for a magazine, so I’ll wait for that moment. There were times where I was kicking it with 2Pac. I chose to wait and now the chance is gone forever.”

Over the years, Estevan lived some iconic moments and wishes he had the pictures to share those memories today. In Estevan’s eyes, words can’t do a moment justice.

When asked about his style of shooting, Estevan laughs. “I got kind of lazy when I was shooting and I think that’s what made my style – because when you’re out there shooting there’s so much to think about, it’s stressful. When you want to get a shot, you have to be quick.” he shares. “On the camera that I was using, there were two knobs that you’d have to adjust. I was like, ‘You know what, I’m just gonna keep the one on the lens at 2.8. And I’m going to adjust the one on the top. I would just focus and then hit the switch on the knob with my shooting fingers. It just gave all my photos that vibe because of the depth of field. And I would naturally frame everything the same way.”

In his now-famous portrait of Nipsey Hussle, the up-and-coming rapper looks fearlessly into the lens without any idea of the success that was about to consume him. The photographs were taken outside in the ’hood that shaped Nipsey, and even though enemies lurked nearby he wanted to be remembered for standing tall on the block. After Nipsey was murdered, Estevan’s photograph was painted in the neighbourhood as a mural to commemorate the fallen star.

Indeed, hip hop artists and other musicians have been a recurring subject over the years. “Because I was managing Cypress Hill and House of Pain, I started pitching my photos to hip hop magazines asking if they wanted pictures of the tour, backstage or whatever.” Estevan would go on tour with the Beastie Boys, No Doubt, Limp Bizkit and The Fugees. He has since photographed almost every legend in the hip hop scene.

Estevan’s catalogue juxtaposes portraits of people who have street fame with images of celebrity. He captures athletes with the same tenacity as a cruising vehicle. He can see through what’s happening and distil a feeling. And the moments he captures have stood the test of time.

“Photography used to be more low key, and kind of harder to do. Now it’s oversaturated. I just love to take portraits of people. I try to tell their story in one photo. Give an insight into their life in one photo. Let their face tell the story. I’m trying to bring someone into the photo. Into the feelings of the photo.”

When asked about his favourite photographs, Estevan thinks fast. “I love my family photos. Some of the low riders hopping in the ’90s. There’s a shot of my friend when he crashed into a telephone pole with his 64, which is the line right out of an Eazy-E track. I shot De Niro and Al Pacino. I shot Dennis Hopper smoking a cigar outside his art studio.” Each memory is triggered by a photograph, a story and a lesson.

In my youth, Estevan’s photographs of gang members felt like they cut close to the bone of life and death on the streets. Estevan would feel the heat as he rolled around with different sets and went behind enemy lines. It was only because he was from that life first that he could gauge the temperature of where and when to shoot.

“One time I was shooting these gang members. We’re in the parking lot at this swap meet. There was a blood gang and a Mexican gang, the gang that I’m shooting. We were in the parking lot and they were like, ‘Shoot us right here, this is where we get all our clothes and stuff.”

When a rival blood gang member rolled into the swap meet, Estevan could feel the heat closing in.

“Then someone said something like, ‘Eh, there’s that motherfucker right there.’ And they’re like, ‘Hey, get the shit, get the shit.’ I saw them grabbing their guns. The other guy didn’t even know what he was driving up into. All of a sudden, they just started shooting. Shooting at him,” says Estevan. “I put the camera down. I didn’t want to take no pictures because I didn’t want to have nothing incriminating. This stuff probably isn’t cool to shoot. So let me put the camera down and let them do their thing. And then we’ll get back to the photos.”

When the smoke cleared, Estevan left with the Mexican gang. “He says to me, ‘You get that shit? There’s your gangster pictures right there.’”

Love Is What You Make It: ‘Love Letters’ by Jordan Drysdale

By Annabel Blue

Atong Atem – A Familiar Face on a New Horizon

By Sophie Prince

Keep my head above water

By Mahmood Fazal

Australian Artist and Designer Ajay Jennings Presents 'Limbo', a Capsule and Photo Essay

By To Be Team

Julian Klincewicz Sees No Moment But Now

By Claire Summers

The Voluptuous Horror of Kembra Pfahler

By Annabel Blue