Nan Goldin's The ballad of sexual dependency

Nan Goldin finds light in the darkest of places. Now 69, she has spent her decades- long career investigating life from the fringes and bringing beauty back to the centre.

For American photographer Nan Goldin, taking photos is like telling the truth. For over five decades, she has photographed her life and the lives of her loved ones in intimate, unsparing detail. Recognised today as one of the most influential artists of the 1980s, her pictures are essential meditations on love, desire, addiction and mortality. Constantly oscillating between beauty and pain, tenderness and brutality, Goldin’s photographs extract light from dark crevices of the human experience.

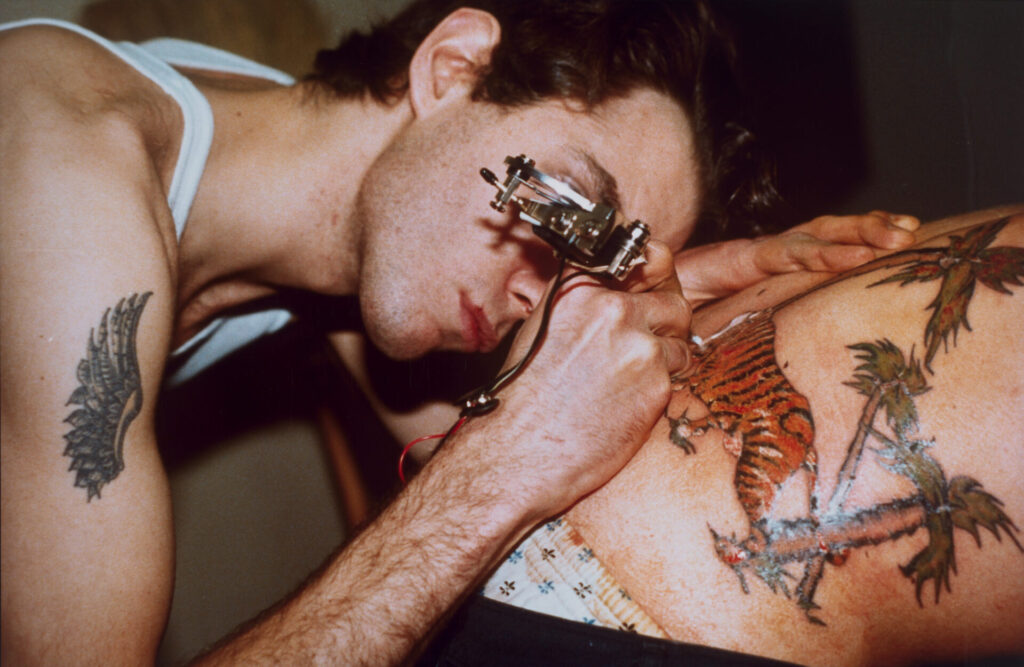

In 1978, at the age of 25, Goldin moved to New York City, where she found residence in a dilapidated Bowery loft. A year later, she began working on what would later become The ballad of sexual dependency (The ballad). The collection of photographs raises a Sisyphean cycle of infatuation, intimacy and heartbreak, an endless falling in and out of love. The ballad depicts Goldin and her friends battling violence and rejection from the abject margins of society. “I’m trying to figure out what makes coupling so difficult,” wrote Goldin.

Recalling a song in Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, The ballad originated as a slide show, built from hundreds of 35mm colour slides. Goldin would hand pick the slides from her own collection and project them onto the walls of dimly lit apartments, bars and nightclubs across the city. Emerging from her own experience living in the dark and dank pockets of Lower Manhattan, these photographs depict Goldin and her friends living life on the outskirts—hanging out, having sex, getting high. We can think of The ballad as a family album, the kind that might be trotted out at the holidays or a family reunion as a post-dinner nostalgic display. I can imagine Goldin and her friends looking at a picture, such as Twisting at my birthday party, New York City 1980, and exchanging their own recollections of that evening. What music was playing? How did that room smell, with the windows closed, forkfuls of food and lit cigarettes at hand?

The slide show culminates in what is perhaps the most harrowing photograph of Goldin’s entire oeuvre: Nan One Month After Being Battered (1984). In this self-portrait, taken a month after she was assaulted by her long-time boyfriend, Brian, she stares into the camera with smeared lipstick, her face bruised and her left eye red with a traumatic hyphema. It is a photograph that displays Goldin’s reverence for the truth. For Goldin, to be free is to be honest about pain; it is only by witnessing the darkness that she can appreciate the light.

Born in 1953 to a middle-class Jewish family, Goldin spent her early years in the suburbs of Boston and Lexington. These were orderly places: scandals were enjoyed in whispers and secrets persisted behind closed doors. In 2022, Goldin wrote, “I grew up in a period in which the glue of suburbia was denial. It maintained the culture, the mentality, the outer face [...] I saw very early that my experience could be negated. That I never said that, I never did that, that never happened. I needed to get away.”

At 14, Goldin ran away from home, escaping suburbia and, to her mind, its suffocating confines. Young Goldin lived a nomadic life, floating in and out of foster homes and communes in the Boston area. It was an act that was triggered, in part, by the suicide of her older sister, Barbara. Years later, Goldin would write, “I was very close to my sister and aware of some of the forces that led her to choose suicide. I saw the role that her sexuality and its repression layed in her destruction. Because of the times, the early sixties, women who were angry and sexual were frightening, outside the range of acceptable behaviour, beyond control. By the time she was eighteen, she saw that her only way to get out was to lie down on the tracks of the commuter train outside of Washington, DC. It was an act of immense will.”

Goldin picked up a Polaroid camera for the first time in 1968 and discovered what would become a lifelong passion for documentation. In reaction to her early experience of loss, photography became a way for Goldin to ensure the survival of the people around her. The medium could shield her memories from the corrosive passage of time.

The ballad has always been something of a living, breathing entity. Throughout the years, it has existed in many forms—constantly edited down, rejigged, and remixed. In 1986, the collection was published as a book by Aperture. By that point, the HIV/AIDS crisis had devastated Goldin’s community, taking with it the lives of 2,710 people in New York alone. The ballad, once published, became a testament to a world fading out of existence.

This year, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) opened its doors to a Nan Goldin retrospective—the first of its kind in Australia. Drawing upon Goldin’s iconic book, the eponymously titled exhibition displays The ballad in its entirety. The Cibachrome prints, thanks to their luscious, metallic quality, approximate Goldin’s original 35mm colour slides. It is as if the NGA has been transformed into a giant cinema, and audience members have been given tickets to see a film of Goldin’s life play out in stills. “We had this beautiful idea of running these prints along the wall—in moments of intensity and moments of quiet,” explained Anne O’Hehir, Curator of Photography at the NGA. “We want people to take the time to connect with these images and to give themselves over to Nan. She wants us to surrender ourselves to her.”

At the NGA, these photographs emerge from dim walls as luminous portals into lost moments and memories. They draw us in, prompting us to acknowledge the beauty of our own lives, in all their messiness and unpredictability. “These photographs unlock a confessional mode within all of us,” said O’Hehir. “And that’s what Nan would want. She’d want us to look at these photographs and think about our own lives.”

I stand before C.Z. and Max on the Beach, Truro, Massachusetts, and see my own memories unfold, when I was the one splayed on a beach towel, drunk on beer, delirious from the sun. These photographs are a reminder of our shared humanity and our impulse to seek out pleasure and connection everywhere we go. For O’Hehir, that is the lasting legacy of The ballad. “It’s a story that no one will ever get sick of,” she comments. “Because it’s about life and it’s about love. It’s about you and I.” Now in its fourth decade, The ballad presents as a precious ode to lost friends, lost moments, lost cities. “Mourning doesn’t end, it continues and it transmutes,” reflected Goldin. “This book is now a volume of loss, as well as a ballad of love.”

One of the most beautiful photographs in the exhibition is Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City 1986, which shows Goldin’s close friend Cookie Mueller standing teary-eyed at the altar next to her soon-to-be husband, Vittorio Scarpati. It is a tender, sentimental occasion—made all the sweeter with Cookie’s buttercream dress and white frosted nails. Unbeknownst to their admirers in the background, the couple would both die, within two months of each other, from AIDS-related complications. But here, photographed, their faces are vibrant in a moment of happiness, held in the amber light. They will not disappear, they will never vanish. As Goldin proclaims, “I made my people into superstars, and The ballad maintains their legacy.”

The ballad of sexual dependency is on display at the National Gallery of Australia until 28 January 2024.

RHYS LEE “PAINT KNOWS…”

By Saša Bogojev

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: The Guardians

By Sarah Buckley

Lonnie Holley on Improvisation and Personal Truth

By Rachel Weinberg

Artists in Conversation: Gabriel Cole and Brendan Huntley

By Rachel Weinberg

Artist Josh Robbins on 'Natural Abstraction'

By Riley Orange

Nabilah Nordin

By Sophie Prince