Making Art Not Love

Making Art not Love

Feature by Sophie Prince

What does love bring to art and what does it bring when it goes away

– Tracy Emin

Artworks that are a direct outcome of heartbreak are not all positioned as such. Many artworks will not explicitly index all of the experiences that went into them – heartbreak or otherwise. So as not to cross-over into gossip, we’re delving into a selection of works that expressly embody the collateral of an artist’s breakup with a partner, bringing together some controversial, labour intensive, intellectual and bodily artworks from across the board – including big names Tracey Emin and Sophie Calle to those currently operating within more experimental circles of Australia, namely Chelsea Arnott and Parallel Park. Across these artist’s practices stylistic, reflexive and intellectual approaches are employed to navigate through a personal experience to arrive at a public message.

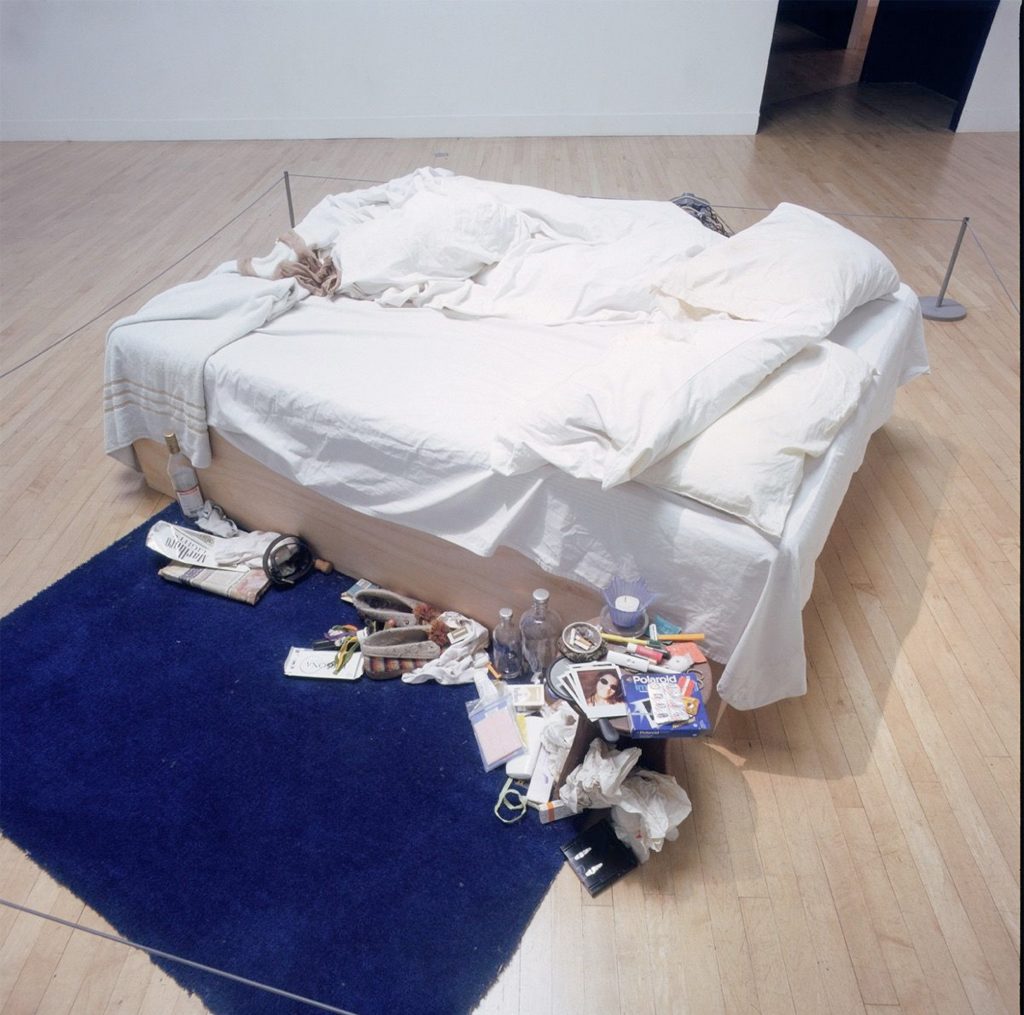

The personal and the subjective psyche of persevering through heartbreak and expressing the process couldn't really be fully addressed without engaging with Tracy Emin’s practice. Perhaps most famously, the artist shocked viewers back in 1999 with her work My Bed (1998) – despite My Bed securing her inclusion in that year’s prestigious Turner Prize. As the title suggests, My Bed is the artist’s bed after a core-shaking breakup that saw the artist spend weeks pent up in her room, stewing over love-lost in increasingly stained sheets. By inserting the bed into the context of the white cube gallery space, the artist subsequently asserted that the bed and all the paraphernalia that the artist had in bed – cigarettes, period stained underwear, vodka bottles, joints, magazines and a pregnancy test – was art.

Critics slammed the work for its unmediated delivery. The Guardian writer, Adrian Searle wrote that My Bed was an “endlessly solipsistic, self-regarding homage”, and not only attacked the concept of the work but also the artist, stating “Tracey, you are a bore.” The biography of the artist is undoubtedly centred in this work, however, the extent to which it is only about the artist is questionable. Historian Laura Lake Smith connotes that My Bed also exudes performativity, Smith discerning that Emin balances an “authentic, inauthentic persona”, which she harkens to the rise of reality TV and media – that in the 1990s was being critiqued for its deliberate yet naturalised messaging. While a more contextual reading of the work than Searle’s commentary, Smith’s interpretation, as I see it, is not particularly ground-breaking because the idea of a work being able to offer pure authenticity or be anything but a deliberate proposition to the public were common sites of contention known by many artists working in throughout west by the 90s – with Dadaism in the 1910s naturalising the validity of the found object and Postmodernism in the 1930s introducing the well formed critique of universal or discoverable truths while championing the gaze of the individual – leading me to think that the work was not claiming to be a distinctly cryptic or rebellious disruption to the ‘meaning of art’ or authorship. Rather, the communion between the imagery of a seemingly stagnant person – specifically that of a woman in the throws of emotional turmoil – combined with the impression of an unmediated (and therefore perhaps ‘unartistic’) vision of life come together to demonstrate a reality of how some people cope with life – which I see as validating but evidently someone like Searle sees as self-indulgent. Feminist readings, including my own positionality cite the push-back of My Bed as emerging from the ‘messiness’ of the work or rather the lifestyle and state of mind conveyed because as even if conjuring authenticity through artifice in the work, the story told is that of an imperfect woman. All of this — the work, reactions and biography — operate as an exemplary context for reflection and subsequent discourse on the expectations of women, femininity, gendered norms and taboos that proliferated through the 1990s and even to this day.

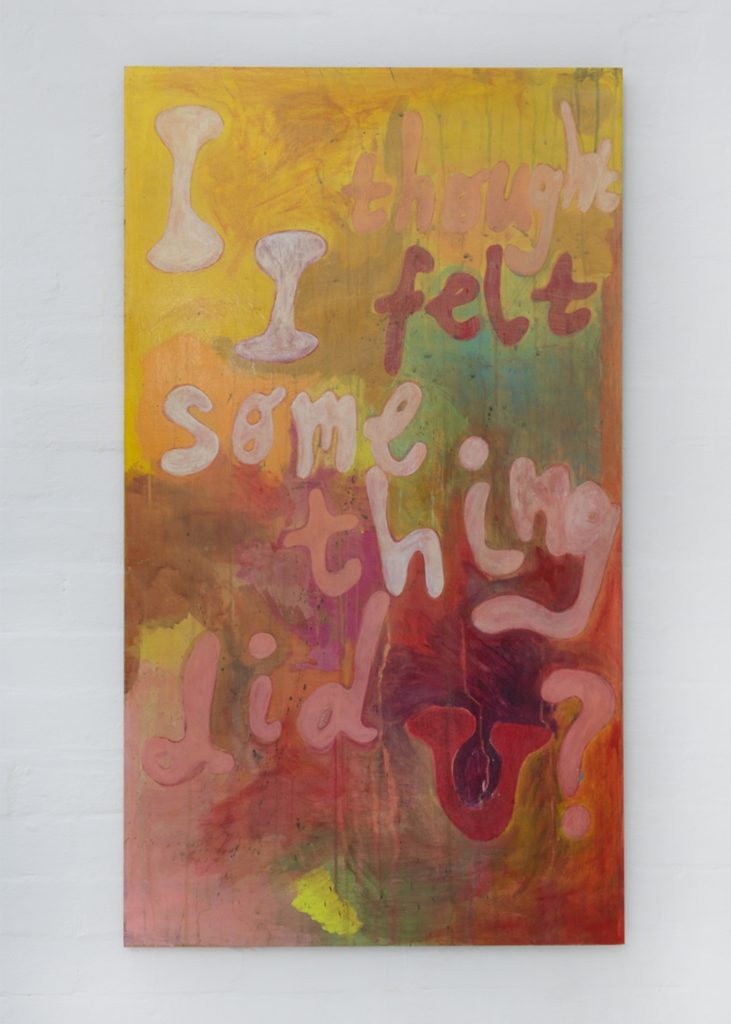

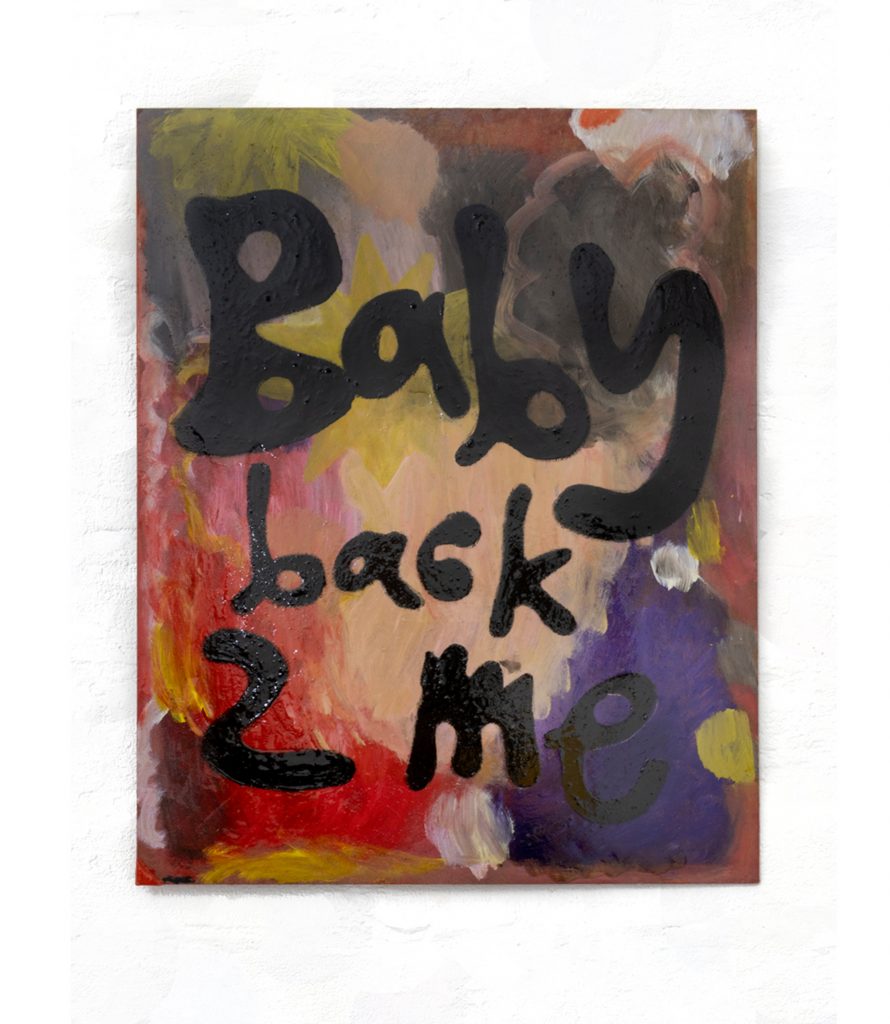

The sense of immediacy in the sentiment and materiality in My Bed is unquestionable. Alternatively, the work of emerging Melbourne-based artist, Chelsea Arnott taps into a common urgency and emotional resonance by harnessing a considered painterly process to specifically grapple with the subject of heartbreak, missed connections and grand gestures. Statements such as ‘Baby back 2 me’, ‘This 1 is gonna hurt’ and ‘I thought I felt something did u?’ are turned into fields of colour, texture and playful graphics upon the artist trawling through her journals, i-phone notes and songwriting exercises to hone in on resonant moments – culminating in the exhibition Half-Memories, 2020 at Artereal Gallery. These mixed-media paintings of statements that vary in clarity (both visually and literally) are ambiguous but also very astute sentiments that I can imagine many people mentally move through on the road to and beyond love. Arnott’s specific experiences of heartbreak are the base of the works, they become generalised or rather, a cliché by offering no context and and referencing disparate moments — the artist notes, “I’m interested in using clichés around love and relationships as an entry point into my work. In particular, I am interested in elevating pop-cultural ways of both thinking and talking about love in the space of art.”

Reflecting upon the reflexive and impulsive origins of these statements and how they are transformed into something interpretative and ‘cliché’, makes me problematise the idea of a cliché. Arnott’s Half-Memories, as well as other text-based works, such as Emin’s prolific neon works, including I Loved You More Than I Can Love (2009), seem to teeter of the threshold between cliché and the broadly resonant – perhaps similarly to a meme or motivational Instagram tile. As I see it, the reading of a sentiment as classic or cliché; an adage or an assumption (so long as it is a novel expression), is very much up to the gaze of the viewer and what they’re looking for or need. Text in art is an interesting union because the words themselves are not the only proscriptive source of meaning — the medium, size, the artist’s hand and colour choice are all tied into how we read the work — creating more context for interpretation and room to play and process for both the artist and the viewer. In Arnott’s work the connection between this reactive recording of her thoughts and her visual language that includes layers of colour applied in varying gestural styles that range from controlled to a broad sweeping handling of mediums and a consistently bold use of colour speak to the mingling of memories and an active deliberation over them that beacon different choices with full conviction in the moment of re-envisioning them. Arnott’s process of obscuring the specificity of her sources of inspiration and heartbreak mimics the process of how with time, intense thoughts become contextualised by your own and other’s experiences, often resulting in some moments buried while other aspects transform into a kind of crystalised ‘lesson’ or feeling. These succinct ideas that the artist brings into focus mitigate being too exclusive to the specific experience of a break-up, as the statements are also intended to speak to the various moments from which heartbreak and the search for reconciliation can emerge.

Do people like hearing someone’s story about how happy they are? Not usually.

– Sophie Calle

Considering the slippage in meaning and memory spurred by time, break-up artworks can cross over into being cringy and diarisic. French conceptual artist, Sophie Calle insights this cross-over when discussing her book Exquisite Pain (2004) that draws upon the experience and analysis of a long-distance breakup she went through in 1984 between herself and her then-boyfriend who fell in love with someone else while she was travelling extensively on an artist travel grant. The book captures the artist recounting and recording her breakup story to any 99 people who would listen throughout her travels. Hindsight, some twenty years later, reframed the whole ordeal as ‘banal’ to the artist. However, even after dismissing the intensity of the feelings she once went through, the artist never discredits the feelings for spurring incredible productivity — in this instance three months of mourning resulted in one exhibition and one book! Calle cites unhappiness as encouraging introspection, “when I am happy I don’t photograph the moment to share with people on the wall of a museum. It doesn’t translate well. Do people like hearing someone’s story about how happy they are? Not usually.” Rather Calle’s rigorous approach to unpacking pain, is in Exquisite Pain quite a revelatory, cathartic and frank. The outcome of sharing this specific experience, like with Emin’s My Bed towards which Emin also expressed personal distance towards in its meaning in a recent 2018 iteration of the work at Turner Contemporary in Margate, is perhaps overarchingly, the conviction and clarity felt in the moment of tapping into profound feelings, even if the feelings and the life enabling those feelings become a distant or even banal memory.

Alternatively, the artist’s 52nd Venice Biennale artwork-cum-book titled Take Care of Yourself (2007) very much distances itself from the emotion of a breakup over email — the work directly cites the email over 100 times, becoming an almost anthropological statement. Take Care of Yourself involved the artist inviting 107 women to interpret a break-up email she received. Beginning with a grammatical proofread by a scholar and then diversifying into psychoanalytic analysis, poetry, crosswords, music, dance and more, the initial event becomes seen through some of the various lenses through which we can choose to see life at large. The result was subsequently published as a book as well as forming the basis of Calle’s Venice Biennale work. Looking at reviews from Calle’s biennale exhibition across various forums and articles, it is interesting to note how many people loved Calle’s installation in the French pavilion. For this installation, the artist extrapolated the context of the book into a myriad of intimate yet sprawling moments to look at and read the responses to the infamous email — the mediums for engaging with the concept vary from tessellating movie stills, a grid of televisions showing readings by contributors, as well as wall-mounted crosswords, letters and poems — immersing visitors who gazed upon the contributions, enthralled. But why? Considering the emotion, intuition and instantaneousness of some previous works discussed, the extensive synthesis of this breakup artwork is notable. Perhaps by offering a multiplicity of female perspectives, the artist relinquishes control, not only of the artwork, but also creates confusion around and distance from the source, and so introduces multiple points from which the viewer can look, not only at a dramatic breakup, but at the idea of relationships and human interaction in such a way that judgement of other perspectives brings one’s own ethos into question.

Sophie Calle’s perception that art about positive moments in love is not a compelling enough subject is challenged by the expanded practice of collaborative group Parallel Park made up of two artists, Hannah Bates and Tay Haggarty. Based in Brisbane, the duo founded Parallel Park six years ago in the early days of their relationship. Their practice began during their self-proclaimed ‘honeymoon’ phase — creating works such as Sausage Sizzle (2015), Tandem (2016) and Sexual Athletics (2016), which they describe as ‘loud’ and ‘poppy’ — Haggarty going on to rationalise this chapter during an In Conversation public program for the exhibition titled Friendship as a Way of Life (2020) at New South Wales Gallery, “at first it was quite explicit, overt, very obvious — ike sensual intimacy, which we thought was very important to have in our work at the time because we weren’t seeing it anywhere and we were making the art we wanted to see in the world.” Exhibiting across Australia in both curated and solo exhibitions, even in the early years of Parallel Park, it is evident that their subject and delivery has contextual relevance and resonance despite embracing sex, love and intimacy-positivity. Looking back on these works, it is pretty clear they are in a romantic relationship, however, the works are not just about themselves — the way they work together with their bodies in works like Tandem or In Time (2017), along with their sense of humour and direct references to sexual identity typified in Sexual Athletics or Boneyard (2016), also speak to themes of closeness, compatibility, tension, duality and sensuality that are non-exclusive ideas.

As I see it, there is no problem with exploring ideas that aren’t ‘for everyone’ or that are not contextualised within a broader landscape of history, however, this approach can limit how ‘successful’ an artwork is in the sense of them aging well in the eye of the artist and viewer. This instability can be seen in the first collaborative work Parallel Park made together, six months into their relationship, Haggarty exclaiming, “it’s buried — it will never see the light of day!” Despite sharing the performance-based work, which involved rolling a vibrator together in space across a wall to create an intense hammering sound, with their Fine Art cohort at Queensland University of Technology, which Bates she goes on to describe as “declaring their queerness to the world”, the explorative delivery, in that the work was an outcome of simply being and experimenting together after-hours at uni, did not encapsulate the same nuance, dynamism, research and rigour that they would go on to integrate in later works.

The research and collaborative principles that Parallel Park have been working within as collaborators seem to be the cornerstones of their capacity to continue to collaborate together post-breakup. In the exhibition Friendship as a Way of Life a number of works from throughout their practice are on display with recent works, including Shift (2020), their first work together no longer as a couple. The exhibition itself explores alternative types of love beyond that of a romantic relationship — and with the inclusion of Shift displayed in physical opposition to In Time the colloaborator’s ability to develop their works and their type of love for eachother are seen in full context. Reflecting upon their first work no-longer as a couple, Bates comments, “Shift is the first work we have made not as a couple and marks a big transition of making together… it really shows queerness and community and these relationships that outlast romantic phases.” Surveying their work so far, it has been the same themes and collaborative integrity that has carried them through the ‘loud’ and ‘poppy’ works to developing more subtle and tender works such as In Time made later in their relationship, denoting that their expanded practice is really a testament to the layers and types of intimacy that are ripe for exploring in life and art. What some might consider to be maturity, I and it seems Parallel Park do too, link to pro-actively thinking and researching within collaboration, queer theory and cultural safety to develop a framework of support that can endure the variances of external changes or challenges. Haggarty highlights the intentionality that went into their relationship shift, to subsequently create Shift, “we started this shift from a romantic relationship into a platonic relationship and we still have this kind of intimacy — it’s about promoting this kind of love and closeness and skill sharing and support — add I think that is one of my favourite parts of Parallel Park’s work.” These changes can be seen in In Time and Shift, whereby the repetition of movement, which is common to their expanded practice, embody slight changes as if bookmarking different stages of their relationship. For example, in Outgrowth, their hands move together, touching, in a clock-like movement holding each other in tension and time, but then when this movement is repeated in Shift, this clock-like movement is further apart, their hands don’t actually touch — but they are still in tension as well as a duality in their movement. By creating a conceptual foundation of intention, repetition and communication within their work, the visual elements move with them to express a relationship that will inevitably change.

The end of a relationship in art is encapsulated forever in all these works discussed — a specific moment captured by the artist is then offered to the world for analysis. As an art historical writer, ambiguity is often the optimal space for literary craftsmanship, harnessing the tools of research, observation and intuition. However, within the context of this topic, research can more closely resemble writing about paparazzi shots for a gossip magazine in the sense that researching someone’s biography and extrapolating their personal life onto an artwork could easily become derivative titillation rather than expansive discourse — perhaps drawing parallels and making claims in such a way is better suited to conversation or an interview. Nonetheless, engaging with commentary and works by Emin, Arnott, Calle and Parallel Park I hope to honour my own interpretations based on research that are intended to no simply speculate on someone’s personal life, but offer entry points for reflecting on on relationships, the function of art, and the notion of ‘success’ in a way that isn’t necessarily resolved for you, but are ideas waiting to be discussed.

The Voluptuous Horror of Kembra Pfahler

By Annabel Blue

The Potent Joan Didion: A Life That Touched

By Katie Brown

to Be Issue 02

By Annabel Blue

CHRISTOPHER POLACK and the art of IMPERFECTION

By Annabel Blue

STANISLAVA PINCHUK: Terra Data and the Land As Witness

By Alexia Petsinis

What To Know About PHOTO 2022 This Year

By To Be Team