Keep my head above water

“A work of art is only of interest, in my opinion, when it is an immediate and direct projection of what is happening in the depth of a person’s being … It is my belief that only in this ‘Art Brut’ can we find the natural and normal processes of artistic creation in their pure and elementary state.”

Jean Dubuffet

In October 2021, award-winning artist and four-time Archibald Prize finalist Benjamin Aitken pleaded guilty to a string of drug trafficking offences and unlawful possession of firearms—offshoots of his spiralling addiction and subsequent breakdown in mental health amid the height of the Covid pandemic. Now, following his conviction and 18-month corrections order, Aitken wants to straighten out the image that the media has constructed of him in his first sit-down interview since his release. So, on a sunny afternoon, we open a bottle of wine, share a steak covered in Roquefort cheese at Poodle Bar & Bistro and discuss Aitken’s artistic origins, reputation and influences, his journey from incarceration to sobriety and its impact on his work.

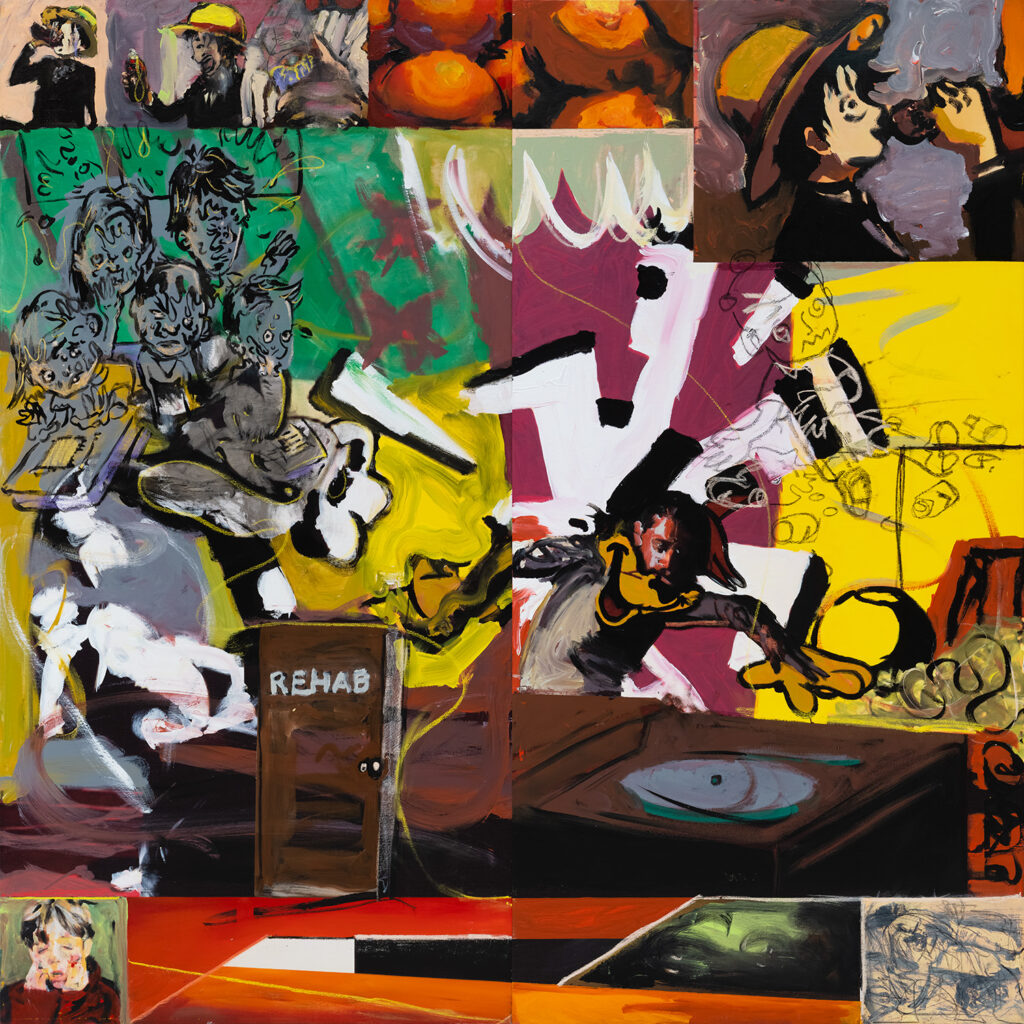

In the Nicholas Building’s PRODUCE Gallery, a five-panel Benjamin Aitken painting hangs as a sobering contrast to the view of the serene Melbourne skyline. The painting, labelled Delirium Tremens (2022), is bookended by two self-portraits on either side of the panels. Shaking, confusion, high blood pressure, fever and hallucinations are among the symptoms of the delirium associated with alcohol withdrawal—a semiology that accounts for the manic ghosts in Aitken’s work.

On the left side of the painting—representative of the logical side of the brain—Aitken’s portrait is clear, encased in a pure white frame with text above his head that appears to have been rubbed out. On the right side—the imaginative and expressive side of the brain—Aitken’s portrait is melting beneath the weight of a black square. The comic-style narrative between this arc depicts a speechless mashing of drunk cartoons, a sketch of a man wielding a shotgun, and a trumpeter tooting the word “forget”.

BENJAMIN AITKEN, Untitled, 2023, synthetic polymer paint, ink, crayon, chalk, mixed media 8 panels at 150 x 75 cm. All images courtesy of the artist

Delirium Tremens is among the most recent and highly anticipated paintings from the controversial artist. In 2021, Aitken pled guilty to trafficking cocaine and ketamine, possessing ammunition, possessing drugs of dependence, and possessing a handgun without a licence. This year, Aitken has struggled to make sense of an experience that is tragically common among those who have encountered the criminal justice system: suicidal ideation. At times when he confides in me, I’m ashamed to admit how desensitised I’ve become to the lag experienced by those who have served time in prison. Imprisonment turns full-blooded men hollow; it drains the colour from their view of the world. After all, ‘freedom’ is a tough word to swallow when there are still so many people—including Aitken’s mates and my own—in the trenches of what we ineptly label ‘correctional’ facilities.

The work is part of a new painting series, the first since the release of Blundstone Enema. Each work completely engulfs us and sheds light on the erratic waves of Aitken’s mindscape. They are uncaged paintings, free to deal with the broken thoughts that illustrate the way he thinks, or doesn’t think, or has been made to think.

The images are mutations of himself: cartoonish, personal and imaginary. Entangled in these versions of himself, Aitken is an escape artist drifting from the experience of imprisonment toward a journey of rehabilitation and self-realisation. The works are simultaneously internal and distant; they are real and imagined, dark and colourful, tipsy and focused, tired and pure.

MAHMOOD FAZAL How did you find yourself entangled in the art world?

BENJAMIN AITKEN I played music for a long time, percussion, [and] I was always into graffiti as a kid. One of my teachers at Sandringham College wrote SIZR for CR Crew. He encouraged me to do some drawings. He really nurtured my interest in art.

MF Were there any painters that had a deep impact on your work?

BA Francis Bacon. I think his work is tormented. I cover up all the trauma I had as a child. I feel like that’s what I can see in his work; also, the homoeroticism. I’ve always struggled with my sexuality. The violence and men in his paintings really stood out to me. Maybe like a turn-on. It was exciting painting. Knowing the era those paintings were made in, the work would have been pretty shocking.

Later on when I really got into text, which comes from a background of working in sign writing factories—making billboards and stuff—I got into Edward Ruscha, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. I was also interested in their prose and poetry.

Especially Jenny Holzer’s truism: “If something is interesting, it’s new.” I thought that was a really cool quote.

MF How did it feel to finally show work after being locked up?

BA It was a bit of a headfuck. I felt really guilty trying to do something to move on with my life when there are co-accused who are going through, and stuck in, the system.

To quote a friend, “You lived a pretty public life on Instagram, posting things you probably shouldn’t have been posting, but everyone was along for this journey. You owe it to people to keep them on that journey.” It’s kept me honest.

MF Is that what it’s about, keeping yourself honest? Who is the work for?

BA My work is just for me really. I’d be happy to make thousands of paintings, even if no one sees them, because I’m just compelled to make the work. If you want to make a living from it you have to put the effort into networking, trying to make sales and trying to be relevant to keep your name out there. If I really had a choice, I’d like it to be a lonely pursuit. I’d have to be doing factory jobs or selling drugs to keep my head above water. Now those things aren’t really an option. And they’re not really good for my mental health.

MF Is there anything you’re trying to say with your work?

BA It’s just visual commentary. I don’t want to be too explicit or literal. I like to let people work out the narrative.

MF Your past is a pretty imposing narrative.

BA I try not to glorify the past. I think I did that with finesse in my last work; I made it more about my own mental health journey.

MF How do you confront that stereotype of the larrikin artist, distancing yourself from the likes of Adam Cullen, the myth of this out-of-control artist on the brink?

BA It’s hard to shake it, I reckon. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to shake that image; what I’ve done and what I’ve been labelled as now… labelled as a criminal who makes paintings.

MF It’s not a new thing in the history of art. Why do those worlds converge?

BA It’s hard to make a living from it. And I guess creative people have impulses to explore counterculture. It’s a part of my upbringing and the people I was hanging out with. Obviously my paintings are an extension of myself, but that’s my behaviour, that didn’t come from painting. It came from my environment.

MF What was your environment?

BA Just a bit of sadness, bit of tough times, bad mental health, abuse as a child. I’m privileged to be a White painter. Don’t get me wrong, the paintings help. I make these works like they are tattoos. Whether it’s a shit tattoo or a good tattoo, it reminds you of a certain time. It’s mark making. It triggers certain memories. All those things tie in together.

MF How did you feel having your story told for you in the papers?

BA It was pretty fucked up. Especially when you’re in a really hardcore prison, in Port Phillip’s Gorgan unit on remand. It was hard because I was isolated from the story, you know what I mean? Being in prison and being in rehab. It’s pretty heartbreaking, more for like friends and family who don’t really understand sentencing in Australia.

One of the older dudes has been in there for eight years, you know. He just said, “The cops will contact you in a few weeks to try and get some dirt.” And sure enough, you know, you get a conference call from the cops. They ask you, or they just start talking about my career, and they try to make it all fun. And then they get to the punch. “It must be pretty scary in there. With all those blokes, first time offender in a max security.”

MF Were you in the MAP (Melbourne Assessment Prison) beforehand?

BA I did two weeks at the assessment prison because of Covid. That’s just two weeks in a cell by yourself twenty-four hours a day for two weeks. If I had had my sentence indication, which was three to five years before I got bail, I would have given up on my career. It was one of the hardest things I’ve done in my life. I held my own. I learnt about time, about the liberties that I’d lost. Don’t waste your time. Leave your mark. Leave a legacy.

MF Your co-accused, the painter Shannon McCulloch, also got caught up in your charges.

BA The situation with my co-accused was the worst thing about the whole thing, man. He was just at the wrong place at the wrong time. He stayed at my house. I couldn’t enjoy life. I couldn’t enjoy celebrating anything. I couldn’t enjoy a good meal. I couldn’t even enjoy having that show. To know now that the charges are dropped, and he’s innocent, it’s massive weight off my shoulders.

MF The recent paintings feel freer in comparison to your previous work. How has being sober changed the course of your paintings?

BA I’ve never painted on drugs. I’ve been known to be a drug addict for a long time. I never paint on drugs, just when I’m drunk, because you’re not thinking too hard—you’re letting those mistakes inform the work, letting the emotion of the music come through. Everything’s amplified by alcohol.

This year, everything turned around. I can still make mad paintings sober. They’re turning into better paintings, I think, more honest paintings because, you know, you mask your feelings when you’re wasted. You don’t want to feel the way you really feel, so you drink or you do drugs, you’re not being honest with yourself. [EXEUNT]

Benjamin Aitken is represented by THIS IS NO FANTASY, Scott Lawrie Gallery and TARS Gallery Bangkok.

Lonnie Holley on Improvisation and Personal Truth

By Rachel Weinberg

Ways of Freedom: Jackson Pollock To Maria Lassing

By Billy De Luca

OPEN HOUSE: A NEW ERA

By Alexia Petsinis

Jason Phu on Latest Exhibition 'Analects of Kung Phu' at ACMI

By Alexia Petsinis

The Institute of Modern Art Presents: Jenn Nkiru - REBIRTH IS NECESSARY

By Rachel Weinberg

Love Is What You Make It: ‘Love Letters’ by Jordan Drysdale

By Annabel Blue