Julian Klincewicz Sees No Moment But Now

Julian Klincewicz has spent the formative years of his career blazing a path of impressive might, balanced ever so perfectly by an insightfulness beyond his years. Spanning music, photography, film, writing and design, the Californian has enchanted us with his distinctive formal treatment: hyper-saturated colourful, low-fi mediums and a paradisal mode of storytelling.

There are several moments during our interview where Julian Klincewicz closes his eyes but continues to speak. His brow is slightly furrowed, head tilted to the side. Even through the barrel of cyberspace—Klincewicz takes this meeting from Los Angeles, I from Melbourne—observing this mannerism moves me. It has the same effect as watching someone roll something sweet across their tongue or hold an object with great tenderness, careful to observe its precise weight and shape. Everything Klincewicz says during our interview, indeed all of his work at large, is imprinted with the same profundity. His responses are sincere, managing to be disarmingly erudite while appearing entirely off-cuff. Sitting in his sunlit home, the warmth of the room is only matched by the warmth of Klincewicz himself.

Klincewicz’s artistic by-line comes out of the gate at a sprint: director, photographer, writer, musician, designer. Though, given our favour for neat definitions, he is often referred to simply as ‘multi-disciplinary.’ Somehow this nebulous umbrella term feels like a poor fit. Klincewicz’s exacting attention toward his subject, the manner in which he speaks about his work, is too considered for such ambiguity. For Klincewicz, compartmentalising or creating clear divisions would be to its detriment. “How can I express or explore this thing in the most effective way?” he asks rhetorically. “In life, I’d like to explore the totality of myself, and that feels multifaceted. The place that I can go to in writing is very different than the place I can go to in a photograph.” Klincewicz commands various mediums that share a unified vocabulary.

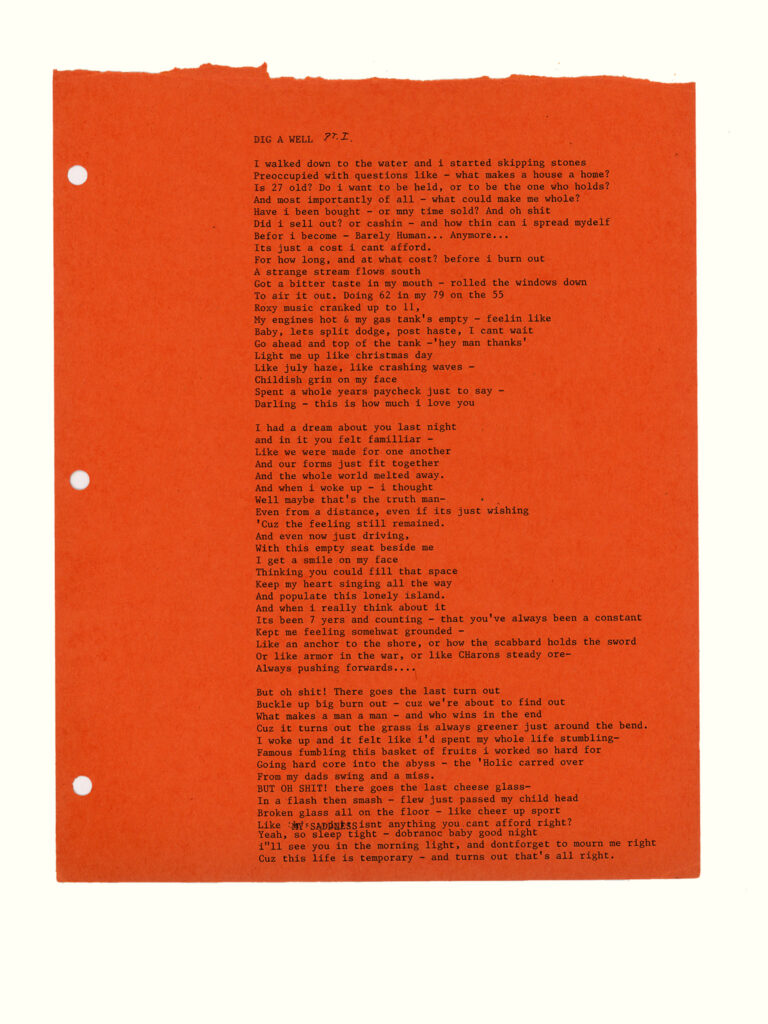

This multi-dimensionality is a hallmark of his practice. He considers each medium as a singular tool, all enlisted in the service of “communicating to as many people as possible.” Every encounter between the work and its audience extracts more meaning. Listening to his music feels connected to the detail that holds the focus of his documentary work, which provides greater depth for a video campaign he’s directed for Miu Miu or Calvin Klein. “I do think that there’s something invigorating and eye opening in jumping around with the kind of work I do, because you bring different information to each different project,” he says. “A discovery you make in music can open up a whole new visual world, and a texture can inspire a written piece and so on. There is this cyclical flow that I feel naturally.” The characteristics of Klincewicz’s work, be it his lyrics or prose, photography or video, vibrates with a hypersensitivity to tone, movement, proximity and light. Retaining a distinctive hyper-saturated colour and thick grain, Klincewicz defines his documentary projects by the act of simply watching. His latest project, a photobook titled Mayhem at Waimea Bay (The Allegory of the Sea), was released in August 2023 and features a series of photographs of surfers, drenched in colour and alive with movement. Deeply personal and the product of an approach that evolved unexpectedly over several years, the project represents a kind of aesthetic surrender.

Klincewicz belongs to a cohort of artists who question what it means to see. Artists like Wolfgang Tillmans, Nan Goldin and Ryan McGinley are titans of the genre. Through their work, these artists redefine how we perceive the world. This particular mode of looking, this focused gaze, is curious and devotional. I share a quote with Klincewicz from a recent Frieze profile on Tillmans, in which the artist says, “I somehow have this sense of history – of the now being history. And of the history of now being possibly rewritten at any time.”11 I ask him if this resonates. He replies, “Everything that we make as artists is autobiography, whether it’s intentional or not, and our sense of autobiography changes with experience.” At this moment, following what the artist describes as a “hugely transformative year”, Klincewicz is conscious of an internal shift, one that disrupts the idea that there need be division or distinct categorisation of who he is as an artist. “I’ve been trying to grapple internally with a newfound acceptance of where I am right now,” he reflects. “I’m asking myself what I can really do that’s going to be interesting in this space, because that’s where I am right now.”

Beloved in the commercial sector, Klincewicz’s work is coveted and celebrated to a degree that has accelerated the trajectory of his career at a dizzying pace. His list of collaborators is both extensive and peppered with heavy hitters. The impact and influence of these landmark projects—his documentary work featured in Beyonce’s Homecoming or collaborating on several Louis Vuitton campaigns with Virgil Abloh—seem to have brought Klincewicz a certain clarity. He wastes no time creating hierarchies or allotting greater importance to particular collaborators. Rather, he appears curious about and eager for collaborations that are born from the affectionate banality of the everyday, ones that come with high profiles and the promise of wide circulation. “Any evolution, whether creative or non-creative, is so tied to community. That has felt increasingly clear and interesting to me.”

We discuss the dated habit of demoting commercial work to a secondary art form. “There are different spaces that art exists within,” says Klincewicz. “Things are just what you make them. It’s just data. Those data points are objective, and what you feel towards them is what is going to dictate the experience. In the right headspace, everything is interesting.” Reconciling the dissonance around the merit of commercial art requires an ability to see the interconnectedness of culture, rather than its division. The argument here is that meaningful work is meaningful work. While context and placement hold significance, they do not solely birth or bestow it. That responsibility lies first with the artist, a responsibility that Klincewicz bears with a steadfast attentiveness. One of the great challenges of artmaking in contemporary culture is the tension between sincerity and commercialisation, and how you maintain the former while servicing the latter. I ask Klincewicz about his relationship to sincerity and if this is a tension he feels. “I’m really trying to explore exactly what I’m called to do, or interested in or inspired by, without feeling any need to justify it.”

After our interview, I take a walk and listen to ‘Pure Michigan’, a song he released in 2022 to accompany a collection he designed for Vans. The lyrics, slung across a composition of languid strings and a plucked guitar, are spoken with a gentle, languorous affect. He says: “Lightning cracks again, electric, and/“and/This is pure Michigan/Bonfires at night/Our joie de vivre/And lust for life/Little stars in jammed jars/And loud men with hot cigars/And the Big Dipper dips to its dawn/As you and I, wine drunk on the shore/Blue jeans and sneakers filled with sandsand.” The chasm between sincerity and ” commerciality may be bridged.

The Vans campaign pays homage to summers spent lakeside in Michigan’s Union Pier, evoking memories of sunburnt cheeks, the pressing weight of midday heat, the boundlessness of children’s games, of clumsy kisses. In this campaign, as with much of his early work, Klincewicz leaned into the heady draw of nostalgia: a past just far enough from the now to be steeped in romanticism, but just close enough that you can still feel it.

In recent years, the focus of his work has begun to slide away from nostalgia, finding itself more firmly grounded in the present. “Ultimately, this moment is the most interesting one,” says Klincewicz. “It’s what we’re called to share.” From this viewpoint, Klincewicz sees the future as expanding before him, vast and unknown. “Recently, I’ve realised I’m trying to get myself naked. To just strip myself of the pretence and the expectation and the fear and the ego and to just bebe. For me, that feels like jumping into a chasm.” No leap is ever certain; in the freefall everything remains possible. Klincewicz has earned that freedom, but what he does with it is peripheral. What matters is the solace of surrender.

1 Wolfgang Tillmans’s Ways of Seeing, Jeremy Atherton, featured in Frieze Frieze, Issue 229, 229

Kingsley Ifill: Within and Without

By Annabel Blue

Iranian artist Shirin Neshat moves between fiction and reality

By Rachel Weinberg

Diego Ramírez

Vampires of the Earth

By Georgia Puiatti

The Institute of Modern Art Presents: Jenn Nkiru - REBIRTH IS NECESSARY

By Rachel Weinberg

The Voluptuous Horror of Kembra Pfahler

By Annabel Blue

Fiona Lee Prepares us for the Unpreparable

By Maree Skene