ERWIN WURM

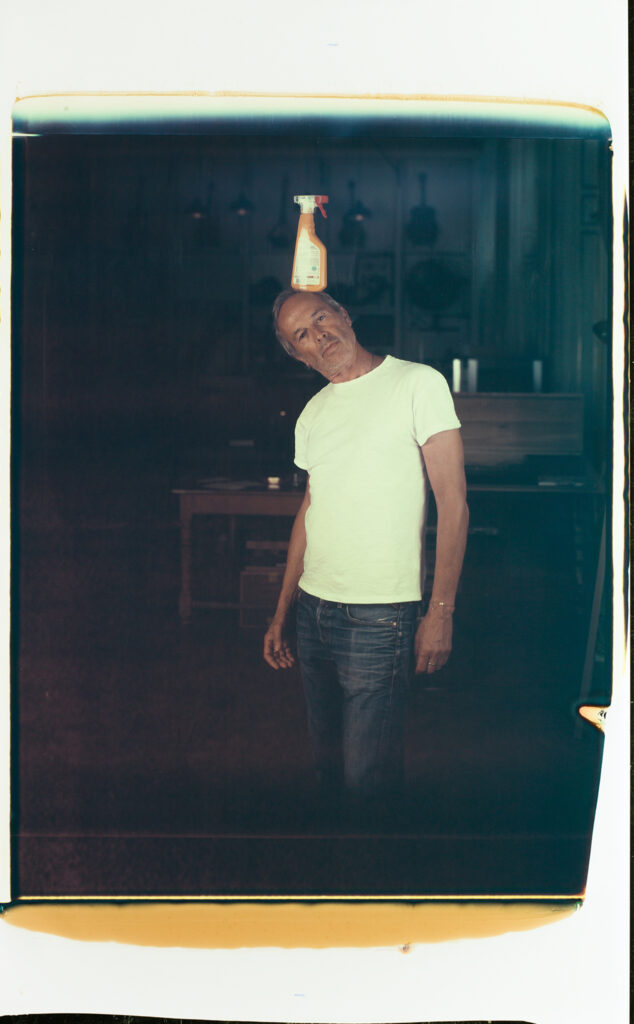

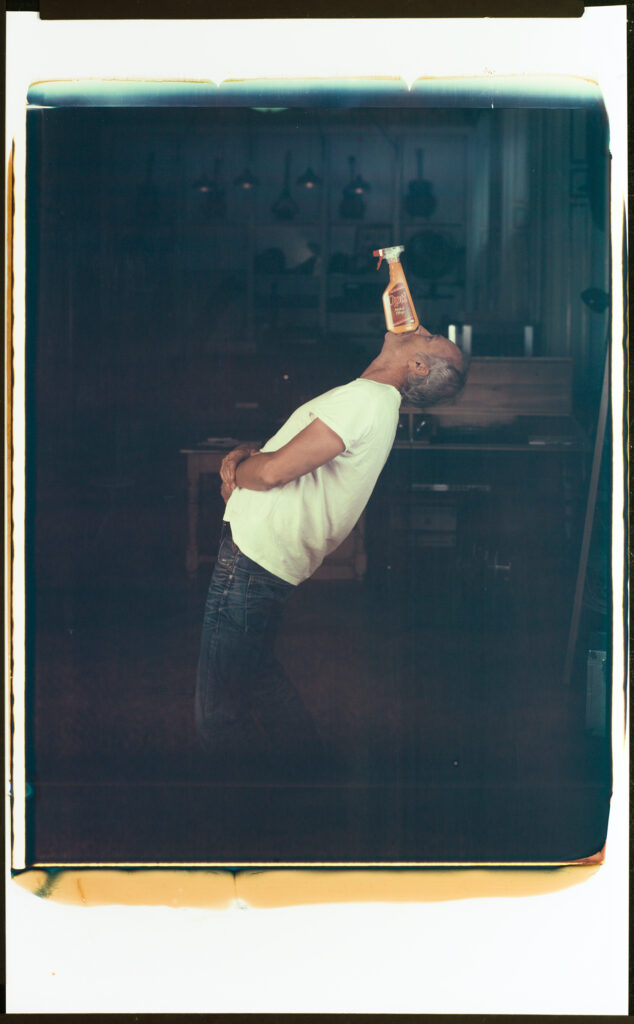

Erwin Wurm is best known for his prominent ongoing series One Minute Sculptures, which began in the 1980s as sculptural pieces involving the public and remains a yardstick for the intersection of performance art and sculpture. Wurm’s other notable works include the Fat Cars series – in which the artist explores the biological and material connotations of adding or subtracting volume and mass – and Narrow House, in which Wurm humorously contorts a version of his childhood home in representation of a melancholic, post-war Austria. Although Wurm’s work is largely interpreted as playful, the artist implores those willing to look to dig a little deeper. While in Greece, Wurm sat down with to Be to discuss his processes leading up to conceptualising work, his childhood in post-war Austria and his disdain for young artists’ entitlement to government funding.

Annabel Blue: Hi Erwin, you’re in Greece right? Are there still fires?

Erwin Wurm: Yes, there are many fires unfortunately, but on the biggest peninsula there is nothing, thank god.

Sarah Buckley: So does that impact your ability to go back to your studio in Austria? Are you working on anything new in Greece?

EW: Here in Greece, I’m making paintings. I’ve never made paintings before … I’ve made similar works, though I call them flat sculptures. They’re very much related to my other work. It’s great here because I get into this flow and I can work very well. And of course, when I go back to Vienna I go back to my sculptures and continue preparing for shows.

SB: What do you have coming up? Are the flat sculptures interrelated with the other works for a particular show?

EW: Yeah, we have many exhibitions coming up – I always say ‘we’ because it’s a studio. The coming exhibitions are in Spain, in Roma and then in Palm Springs in the United States. I don’t directly prepare work for a specific show, but I continue to level up my body of work and then when I have a show I decide which pieces should go where.

AB: Can you tell us about your research process in the lead up to making works?

EW: Yes, I am reading constantly and developing ideas constantly, but slowly. When I have an idea, I’ll draw it down in a little booklet and then after a certain time I go back to it and check what is good, what is less good or what is not good at all. And then sometime later I decide what I should do with the ideas…

SB: How did Fat Cars come about? Which company did you use to make them?

EW: The first Fat Car we made was in 2000. It came into my mind because my work is based on the notion of sculpture, so I thought, “What does it mean to make a sculpture? What is the meaning of sculpture anyway?” It’s about mass, volume, skin, surface, time, all of that. The second strong line in my work is social issues, because I’ve always found that if you only work from the arts to the arts it can be a bit empty. Getting back to the Fat Car – when I was trained as a sculptor, we had to make classical sculptures in clay, adding or subtracting the volume of clay. When we as humans gain or lose weight, we do the same. We add volume or we take volume away. So one could say that gaining or losing weight is a sculptural work. Fat Cars is about that. In a way, I combine two systems: the biological and the technical. The technical system doesn’t gain weight and grow, the biological system, however, does. But when I combine those two things, what happens? What is the outcome? Is it a creature, indicative of how we will possibly end up in the future? When technology has advanced so far that it combines with us biologically…?

AB: I was also thinking about the element of gluttony … The more material possessions we gain, the more gluttonous we become. And in turn, there’s bloating in a metaphysical sense.

EW: Yes, it’s so funny because when I started this work, I had specific social and sculptural interests, but then the works became a synonym for our society. For this hunger for growth, for getting bigger and better. Which is sick. We have to get rid of this mentality in order to rescue our world. So all of a sudden, these pieces became a symbol of consumerism – which is all too much, what we have now.

SB: Yeah, it seems quite multifaceted, doesn’t it? On the one hand, you’ve got the social connotation, usually a negative, attached to gaining weight in a physical form, but on the other hand gaining weight materialistically is always idealised.

EW: Exactly. And with the One Minute Sculptures, a series I started in 1992, I invited the public to be a part of each piece – they had to follow my instructions to realise the piece, and then I’d take a Polaroid so as to have something tangible, beyond the ephemeral act of doing a sculpture for ten seconds or two minutes or so on. But the photo is also a kind of an artefact.

SB: Were you already taking photos prior to the One Minute Sculptures or did that come out of necessity – out of wanting to document those artefacts?

EW: I did some photography before, but it was other stuff and not so intense. With the One Minute Sculptures, the photography came through video. I made a piece in 1992 called 59 Positions. In it, you see me and a friend in a series of different clothes – I filmed the video, and every position is just shown for eighteen seconds because I wanted to show that under pieces of clothing there was a person. When I saw the stills later on the camera, I found them so beautiful. So that brought me to photography. But the first One Minute Sculptures I did were snapshots enlarged very cheaply. Very bad quality.

SB+AB: [Laughs] I think that’s the beauty of them, it adds to the charm.

EW: Yeah, I know. And still I have the feeling I’m a bad photographer. I was conscious of it, but it was bad because I couldn’t do better [laughs].

SB: The way you speak about your practice and your research process almost seems opposite to your art. You use humour and frivolity in your works, yet you come across as incredibly introspective and serious in what you want to deliver. How do you find the balance between the two?

EW: Maybe it’s a part of my personality, because we all have various personalities. Mostly, I’ve realised a body of artwork is very much related to the artist and their personality. There’s a very thin red line that I do not want to step over – I do not want my work to become ridiculous and just hilarious or just funny. I’m not interested in this and so I am aware of the danger. I often use the absurd and the paradox related to the theatre of the absurd, drawing on European and American writers. It’s a specific view on the world.

SB: Can you tell us about Narrow House?

EW: So, my parents built this house in the beginning of the 1960s in Austria. I was born in 1954 and I grew up in a post-War society, which was rigid and hard and, in a way, not free from fascism – it was still a strange society. Narrow House reflects this because to make the house narrow I squeezed not only the house but also the furniture and everything else in it. When you go inside you immediately feel claustrophobia. This reflects Austria at the time I was growing up. Some people come and say, “Oh, it’s so funny, this narrow house.” But I don’t think it’s funny at all.

AB: Well whether it is or isn’t humour at its core, people are intrigued enough to be reeled in, and can subsequently explore the deeper context and meanings of your artworks. That’s what I love about your works, they capture the viewer and then you let people delve into ideas on their own volition.

EW: Yes, that’s what I’m hoping for, that people are not only getting the initial laugh – a Fat Car, ‘ha ha’, a Fat House, ‘ha ha’ –and then moving on, but that they also do exactly what you describe, go deeper and really experience it. That would be the ideal observer and the ideal visitor for the pieces.

SB: Your career has spanned a few decades now. How do you feel about making art in 2021 compared to the 1980s or earlier?

EW: It has changed – I’m much more secure now than I was at the beginning. I was very unsure, I was always with my doubts and I still have doubts, I’m still fighting with what I’m doing. I think that’s very necessary. Artists can be too sure and too self-confident about what to do. As far as the political climate is concerned, I haven’t felt anything negative with my work because I was always very careful with things, for instance I never photographed naked women or men. I always had the feeling, “I do not want to do this for my artwork.” And I only once had a model or two models with naked breasts in pieces. But what I did in the 1990s – I made a photography series called Instructions On How To Be Politically Incorrect. They were pieces related to the world of George W. Bush and his restrictions in the USA – I made pieces called Two Ways of Carrying a Bomb, things like that. But when I tried to show them in the States, people didn’t like them at all, they were not open to criticism of their society. With Narrow House, they wanted to show it in the States and it was a big problem because there was no wheelchair access. And then I had this upside-down Biennale truck where you could walk up through the truck and stand on top – Public Forum in the States wanted to show it, but then in the end they showed something else because it wasn’t wheelchair accessible. They suggested we build an elevator close to the piece, but that would have changed it dramatically, so I gave up.

Erwin Wurm, Melting House, 2009, wood, styrofoam, resin, paint, 125 x 290 x 260 cm

AB: Do you ever find that you have to compromise your work?

SB: Like for the context of the gallery space or …?

EW: There are restrictions, of course. There are limits. My age is a certain restriction and a limit in a way. The art market and the art world change constantly, with the intense influence of auction houses and the very big galleries. This influences everything a lot, especially for young artists. It’s getting harder and harder for them to show their work. What I always found strange is a system we have in Austria – they have it in Holland too – with the state supporting artists. They give them a little money and buy pieces off artists every second year so they can survive – hardly, but still something. But I always thought it made the artist weak because many artists now believe that the state is there to give them money. I would rather see the state make a framework, like selling art tax-free. Then more people would buy art and nobody would have to go to politicians with an open hand saying, “Please give me something.” This corrupts the system. I’m very much against it. But whenever I say this, I get an unbelievable shitstorm [laughs].

SB: You were saying that Narrow House was a representation of growing up in post-War Austria. Do you think that upbringing has influenced your works in other ways?

EW: Austria was such an interesting mixture culturally. There was a monarchy for 700 years, so it was a very strict state. There was aristocracy and bourgeoisie and then a lot of military and other people who worked for the state. This was the one side. The other side was the Catholic church, 2000 years of it. So the Austrian character was influenced heavily by these two structures. At the beginning of the 20th century, when everything broke down – the monarchy collapsed after the First World War – everything came out. All these artists and philosophers – Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler and so on. It was a vivid, very interesting time – there is a lot of interesting history in Austria. My father was a policeman and my mother was a housewife. Nobody was interested in art. My family is full of engineers and doctors, and I was the first one interested in art because I started to buy booklets when I got my first pocket money at the age of twelve. I started to read literature and it opened doors into another world, and I conquered the arts. For me this was my own world, where I could just be and hang on with my thoughts. It was very important to me. I was a professor for several years, and I told my students that it’s not interesting when your work is just about your grandma’s feelings. But if you’re able to transport this connection to your grandma to a broader context then it could be interesting. Which is exactly what Louise Bourgeois did. The issue of her father was following her entire career and she was constantly addressing it – it was the gasoline for her work because it burned her, in a way. So that’s always my goal: investigating the society in which I grew up – my father, my family – and the relationship between literature, philosophy, art and this so-called small bourgeoisie society. This interests me a lot and my work has been about it my entire life.

erwinwurm.at