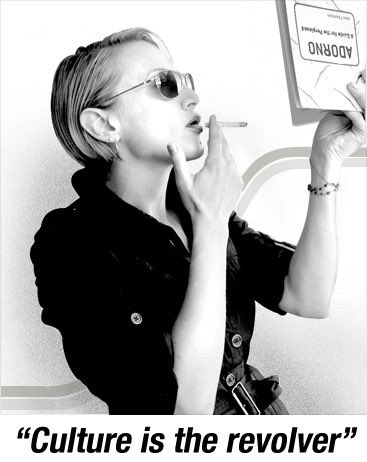

Cintra Wilson

The World’s Most Influential Fashion Critic

The fashion industry has has never seen a writer quite like Cintra Wilson. For the better half of the early noughties, Wilson was the fashion journalist du jour. According to Anita LeClerc, a former editor at The New York Times, Wilson was the most influential fashion journalist in the world, which is why they had to fire her. Wilson had an unapologetic affinity with the political undertones that permeated the fashion industry. She was not afraid to “be more critical than a shopper,” as she puts it. Not only is it how she earned her credibility, but it’s also the reason her words transcend time and retain their relevance. Her poignant and witty prose leaves readers both in hysterics and wishing they might have written it themselves. Wilson was, and remains, everyone’s favourite rule bender—a true “punk,” as she says. to Be sat down with Cintra, seltzer in hand, for a Friday night Zoom rendezvous in San Francisco. Talking about all things ‘Critical Shopper’, cultural politics, and everything in between, Wilson was everything we might have hoped for and so much more.

Annabel Blue: Hey Cintra, thanks for meeting with me. Let’s start from the beginning. Can you tell us about your experience at The New York Times and your column ‘Critical Shopper’?

Cintra Wilson: That job was really a fluke. My friend, who was the male counterpart to ‘Critical Shopper’ said they were looking for a new female critical shopper. He recommended me because he had seen me out once in a Gucci pinstripe jumpsuit. Then the editor at the time, Anita LeClerc, reached out to me and I was like, “I actually don’t have any credentials, I have no idea what I’m doing, I’m not even in that tax bracket.” [Laughs] I lived in Brooklyn and had never even shopped on Madison Avenue. She was like, “Great. That’s exactly what we want.” She had read one of my books and really loved it. She wanted a writer with an outside voice. I got lucky that I had a champion in this editor, who was my favourite editor. I worship that woman. I lived to please her [laughs].

AB: That’s kind of cool though, because you had a different perspective on fashion. I feel like a lot of fashion journalism now is regurgitated.

CW: Yeah, this is what Eugene Rabkin and I spoke about on his podcast StyleZeitgeist. I feel like in fashion journalism now, there’s no more criticism. The capitalist hegemony has finally taken over and taken out all of the critical thinking and critical voices.

AB: Totally, and everyone’s censoring themselves now too. I think that’s a major wet blanket for fashion journalism and creativity at large.

CW: Very much so, yeah. I would hate to think of what I’d be doing if I was still writing for The New York Times, because everything has gotten so inflammatory and everything is so offensive now. If you’re saying anything, you’re going to offend somebody, and you have to not be afraid to do that. People really kick you to the curb nowadays for anything you say.

AB: Is that what happened at The New York Times? Can you tell me the story of why you got fired?

CW: Now, that was a much more complicated dilemma. I mean, when I got the call that I was fired … one day Anita called me up and said, in her own words, “I want you to know something. You are the single most infl uential fashion critic in the world. An article came out today on this blog … And also, you’re

fired.” I’m not going to name the blog.

AB: Did you read the article?

CW: Yeah, and then it disappeared. The article was taken down and I was fired. I heard a rumour that Cathy Horyn had gotten upset that she was number two [laughs].

AB: That is so brutal [laughs].

CW: I think they wanted to get rid of me for a while. I was writing too much social criticism with the fashion stuff and I wasn’t pleasing the brass.

AB: Yeah, I want to read something truly shocking nowadays and can’t find anything.

CW: An editor has to let you do that, in my opinion. Somebody has to give you permission to actually write how you want to write. Anita LeClerc gave me that. People are so concerned with keeping a job, journalism is a shitshow right now. I mean, there are no jobs, no work, so much less money than there used to be. Then following that, the internet. Everyone can be a writer now.

AB: Well, everyone has a microphone, and so many can’t substantiate what they’re preaching [laughs]. What would you say to young aspiring journalists?

CW: [Laughs] I have a pretty thin view. People write to me all the time and I have the most terrible things to say about journalism, and publishing small letters in general. It’s not what it used to be. The opportunities are very rare, and for the most part people aren’t going to let you say what you mean. From what I can see of to Be, you have a really strong vision and content that you can promote in your own way. That’s what you have to do, you really have to be your own voice and your own champion and put together your own projects.

AB: Yeah, and I guess it comes down to finance as well for a lot of the big magazines. The process of building something new and getting enough revenue for the next issues when you’re a baby magazine is crazy.

CW: I’m sure it is. And that’s another reason why I’m sure there were many reasons I got sacked. I think it was because I offended people like Reed Krakoff, who I think withdrew some big advertising dollars. Also, people didn’t used to be such babies. People used to be able to withstand criticism. I mean,

I reviewed Topshop one time and Prince Philip got offended. I’m like, why are these people so thin skinned? You’re a multinational corporation, just shut up. I did always try to be constructive. I was never just hating on people. But also, you want to write something that’s actually interesting to read.

AB: People don’t want to read something that’s full of niceties all the time.

CW: Yeah, everything I read these days is like a PR sheet regurgitated.

AB: I couldn’t have said it better myself. I guess advertisers have a monopoly over content now. But not us.

CW: Content used to drive advertising, now advertising drives content.

AB: This is shifting the landscape. I guess it’s kind of happened with the rise of social media as well. There’s a shift in what we can and can’t say or even make, especially for artists.

CW: It’s amazing to hear about this from a young person. It’s so true.

AB: You have to censor yourself frequently, or most people do.

CW: I’m starting to really wonder about this ‘woke-progressive-intersectional-feminist’ type of stuff. Like I say, we’re all down to support LGBTQIA+ people. But the language requirements now are so tetchy. Everyone is so fussy about pronouns, which they should be, but it seems like no one is allowed to get them wrong. Then cancelling comes as a result. I mean, having been called out for things in my career, I can relate to not wanting that. But if you really want to say anything as a writer, you’ve just got to do it on your own terms.

AB: Can you tell me about your book Fear and Clothing? I heard you went on a bit of a cross-country expedition for it.

CW: Yeah, I wanted to explore how the political economy is actually affecting the way that we live our lives. How personal does it get? I realised it is profoundly personal. And yes, it is in your underwear drawer. There was already this enormous rift happening between red states and blue states in the US. I really wanted to go to some red states and see how different they are, and why.

AB: What was one of your most memorable interactions?

CW: It always comes back to this one guy who really impressed me at the Kentucky Derby. He was a busboy in a restaurant, except he was a Black guy in his late forties and he had incredible, incredible style. He was wearing this beautiful white top-hat. He moved so gracefully, carrying a tray of glasses, not spilling a drop on himself at all. He looked so elegant. You could tell he’d probably at some point in his life been like a hustler or a dice player.

AB: Can you tell me a little about your time living in New York?

CW: New York has changed ridiculously. There was a lot of funk and grit and danger about New York when I moved there and that was really where I wanted to be. New York was perfectly filthy in the late ’90s. It was really a wonderland, and then it just got wealthy. All the funk slid off in favour of high finance.

AB: Yeah totally, every time I visit New York it’s changed substantially.

CW: Yeah, back in the ’90s, New York actually had a soul. There’s no rebellion anymore. I mean, it’s like you don’t have a language for subculture rebellion anymore, sartorially speaking. There’s not even a language of rebellion in clothing.

AB: My last question actually ties this all up nicely, I think. What do you wish you knew back then that you now know?

CW: It’s funny, because you go through a lot of phases. I’ve been a journalist for thirty-four years. If editors over-edited me, I just pulled a piece and walked away. That was important for me to do. There is a certain freedom you can have within certain structures, but you have to look for it. I’ve always learned a lot from really good editors and they can be very invasive, but you learn something from other editors too. Also, don’t be afraid to find the humour in things, it makes people nervous. I was really happy to see your magazine though. It feels like there’s some hope [laughs]. [EXEUNT]

R.Bliss’ Latest Book is a Declaration of Love

By Rachel Weinberg

Harrison Ritchie-Jones and Michaela Tancheff’s CUDDLE Disrupts The Dance Medium

By Laura Tooby

Lola Bebe's Unbound Beauty

By Shannan Stewart

Vans Launches 'Always Pushing'

By To Be Team

JW Anderson Lets Bygones Be Bygones For Fall / Winter 2024

By Poppy Oliver

MARTIN by HUGH: A Curated Exhibition of Martin Margiela's Archive

By Annabel Blue