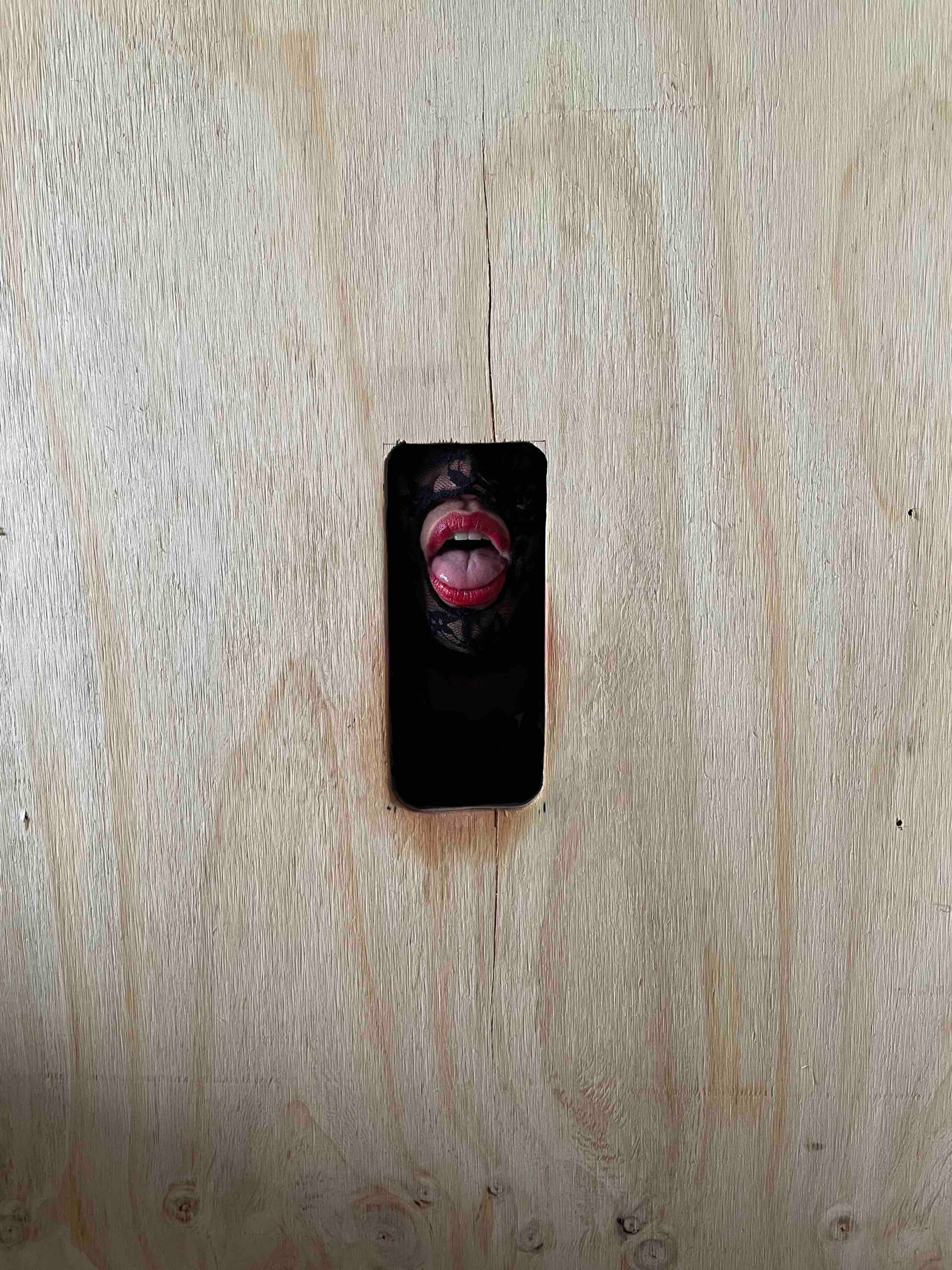

Babydilf on Sex, Love and Glory Holes

Emil Cañita is known online as babydilf. The queer Filipino immigrant, sex worker, rape survivor, pornographer, sexual health professional and lover are most recognised for their documentation of their private glory hole, as well as their cover for Butt Magazine in 2023. People might not notice Cañita's worldly sensitivity, which is a result of their desire to comprehend and accept everything around them.

Cañita’s graphic and candid photographic work is complete with wrenching typography and horny imagery that is ready to move, amuse and entice. Their new body of work, At First I Was Afraid, opens at MARS Gallery on February 29. Sat over a glass of chilled red at Melbourne’s City Wine Shop, fellow artist Mark Bo Chu probed them on their extraordinary lives of sex, love, art and porn.

MBC: Day to day, what role does your art play in your life?

EC: Life is a work of art. There’s so much creativity in what we do just to survive, just to cope with the everyday. It’s how I see everything I do—this is a work of art.

MBC: Is that a choice?

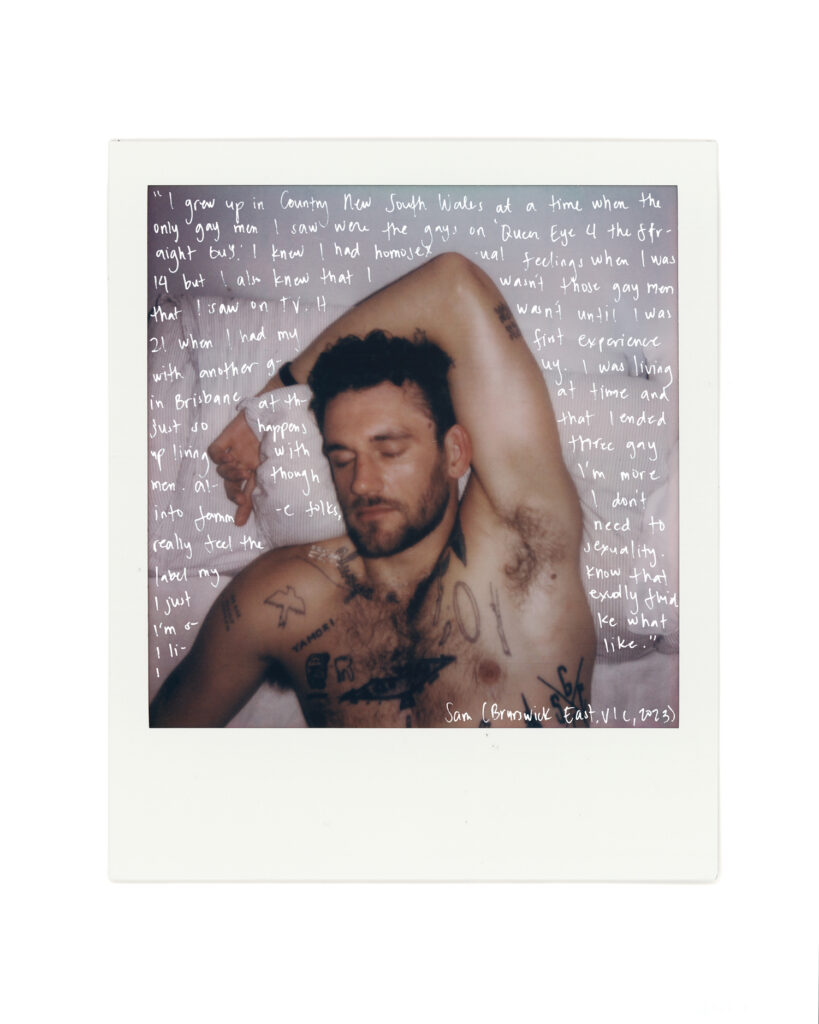

EC: When I first started doing Instagram, six or seven years ago, I’d just started seeing a psychologist. He asked me to do some free writing, to write what was on my mind, which I found really challenging. What I did instead was write about the people I have sex with. For the first two years, I’d take photos of just a hand or a sock to keep as a memory. Then I started posting what I wrote about my visitors. I got so many comments and it just all developed. One year, I started taking polaroids. Only in the last three years have I really built an ethics framework around it all. It’s been a beautiful process.

MBC: Were the first people you posted online clients?

EC: No, just hook-ups. I started to do sex work when I was eighteen because I got kicked out of my home for being queer. It was mostly for survival then. In Brisbane, it was hard. It was rough. You get a lot of racist clients with racist fantasies. Now that I’ve grown, I know how to talk to people better, I’ve got more agency and I feel more empowered in the process.

MBC: How did you end up in Australia?

EC: My mum got married to an Aussie guy in Hong Kong. I grew up in the Philippines, but he’s been in my life since I was nine. When I was in high school, she was working as a singer in Hong Kong and decided she wanted us all to migrate to Brisbane to set up a better future. In the first year, we were at this pub in country Queensland and I had my first experience of racism. Me and my mum were lining up at the pub to get food and when it was our turn, the amount of food they gave us was less than half. I was surprised. I was like, That’s not right. So I look at the woman and say, This is wrong. She just looks back at me and says, That’s what you all get. It really upset me, not because it happened to me, but because it happened to my mum. I remember walking out, going to the car, crying and saying, ‘They shouldn’t treat us like that’. But [my mum’s] husband’s response was, ‘You guys better get used to it’. It gives you a beautiful portrait of who this person is.

MBC: Did you ever understand your mum’s affection for him?

EC: It’s classic Filipino culture. There’s a term called utang na loob, which means emotional debt. Because of what he provided, Mum felt indebted to him. Even for the access to being in Australia.

MBC: Is there a colonial undertone?

EC: There’s a huge colonial undertone but it’s the reality for a lot of Filipino wives. In the Philippines, people go on ancestry.com. The moment they find out they’re twenty percent Spanish, they use that as racial capital. I remember meeting this Filipino guy in Brisbane who found out he was part Russian. So now he introduces himself as Russian. But, like, he looks and sounds Filipino—he grew up there. (Laughs.) It’s so sad.

MBC: Do you think Western ideas of romance and love apply to your mum?

EC: I read All About Love by Bell Hooks a couple of years ago and it really changed my view of love. Hooks frames love as a ritual connection that is built on improving each other’s spiritual knowledge. My mum and I don’t have that connection. I don’t love my mum anymore. Her relationship with love is very materialistic—not that that’s a bad thing. It’s just a very different way of communicating. I guess we have very different values.

MBC: Did her value system, and maybe even her connection with her partner, give you the opportunity to develop your value system?

EC: A hundred percent. I’m very grateful I have access to therapy. I’m grateful I studied sociology, which made me more fearless. I majored in health and society, which is why I work in the HIV sector.

MBC: I saw you return to the Philippines recently.

EC: It was confronting—it had been eleven years. But it was also really nice because I was able to come back to my family as the person I am now. For a lot of them, I became the facilitator. There were all these grievances. In my family, people didn’t want to talk about things that were uncomfortable. Mental health in the Philippines isn’t something people believe in. Depression is not a concept. But these are feelings or experiences anyone could have. Or at least terms to frame the symptomology. With my family, I apply what I’ve learnt. I talk frankly and openly, and it’s been really helpful. They’ve started to understand each other better and have more peace. It’s nice to leave the family that way.

MBC: It sounds like your education really helped them. Do you think your mum’s mission in Hong Kong was to find a way to improve your life?

EC: She’s extremely selfless. To the point that she doesn’t have savings because she sends everything to the Philippines.

MBC: Do you feel emotional debt to her?

EC: From me to her? Not anymore. I distanced myself from her so she could realise that I’m not here to look after her shit when she’s older. She needs to do that. Her family disowned her but guess who she’s sending all the money to?

MBC: Does she believe you betrayed her??

EC: I don’t really know, and, to be honest, I don’t really care. I just want a life that aligns with my values and is surrounded by people I love. I was very honest with her when I cut her off. She told me, ‘I don’t want you to have the same life as me.’

MBC: In a strange way, with your insights, you are kind of squaring up your utang na loob, going back to the homeland and repaying the debt.

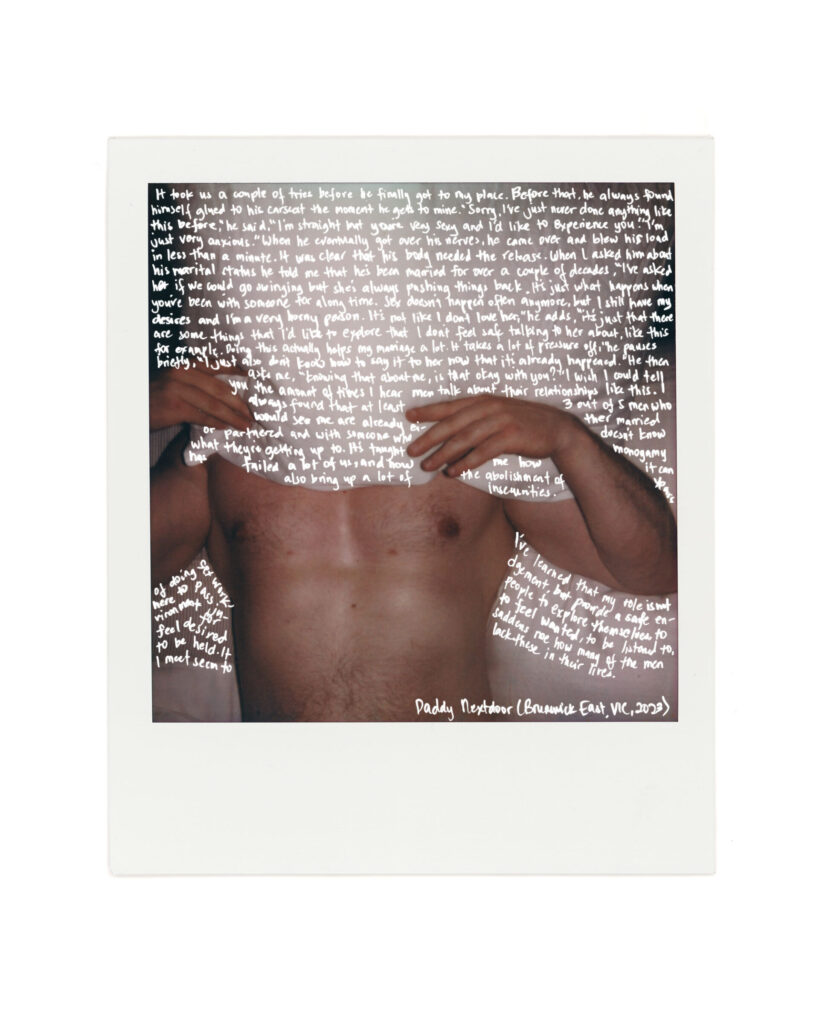

Edition of 6 + 2AP. Image courtesy of MARS and the artist

MBC: The title of your new exhibition—At First I Was Afraid—is taken from Gloria Gaynor’s song ‘I Will Survive’. The lyrics are about transcending an abusive relationship.

EC: The song is about being able to reclaim yourself. So much of the work I’ve done relates to me being raped as a kid. It happened when I was 9 until 13. I hadn’t talked about it until I started therapy when I was 26. Then it took time to process. There was so much to unlock about who I am and my sexuality. Then the glory hole happened. And my life just flourished. Every aspect of my life. Social. Economical. Work life. It just all flourished.

MBC: Sexual.

EC: (Laughs) Sexual. A hundred percent. A thousand percent!

MBC: Are you looking for justice?

EC: I’m looking for peace. And forgiveness. I’ve forgiven a lot of those people. I’ve accepted the realities of what happened. I don’t hold it against them. It was a very abusive family. I was the youngest. The most vulnerable. My stepdad was an alcoholic. I was beaten from when I was in kindergarten. Physical abuse every day. I remember when I was nine, being young and stupid, I was trying to commit suicide with a pillow, but I couldn’t. Now that I’ve been to a doctor, I know you can’t actually do that—it’s impossible! But I remember, as a kid, I couldn’t do it, and I promised myself, if I ever get out of this, I’ll have a life that’s opposite to what this is. I feel like I have that now. I guess it’s kind of about justice. I’ve found peace.

MBC: What else resonates about ‘I Will Survive’?

EC: There’s the camp element too.

MBC: So, what is ‘camp’?

EC: Camp is generous. There’s something about that song that’s so honest and full of life. So present. It’s in every drag queen.

MBC: Is there an element of irony?

EC: There can be. There’s darkness too; a dark humour and sass. It’s a powerful sass, but there’s also a grace to it. And beauty.

MBC: Is the work you do camp?

EC: Is the work I do camp? (Thinks)

MBC: Aside from appropriating the title.

EC: It can be. The ridiculousness of how many guys I’m showing, like the thirty-eight guys that I’ve fucked with. The fact that I’m selling other people’s nudes. That’s a bit camp. Anyone can practise camp. It’s the creation of something out of nothing. Putting a lot of fake Louis Vuitton stickers all over your body could be quite camp.

MBC: I guess they’re conventionally tacky if they’re fake.

EC: There’s definitely a tackiness to camp.

MBC: So, it’s sort of inverting tackiness to semi-glorify it.

EC: You know Juicy Couture? That can be camp. But it’s like, how do you present it to be camp.

MBC: Von Dutch.

EC: Can be camp.

MBC: Can you be camp accidentally?

EC: It happens on reality TV all the time. It’s so camp but the people are unaware. And that’s what makes it camp.

Image courtesy of MARS and the artist

MBC: We’ve barely talked about your art. The glory hole archetype is anonymous, and you’re not anonymous with your clients. What’s the deal with that?

EC: I love querying the idea of public and private and challenging the binary of how people look at things. Private, public. Anonymous, discreet. Let’s just mess with it. Why deal with dichotomies?

MBC: Are your clients, co-stars and artistic collaborators hip to your theory? When they go to the glory hole…

EC: They just want to get off. But because I’m so visible about my work, they know what I’m about. It’s purely fun. And we can make art from it too. At the end of the day, it’s about making a new experience for you and for me and hopefully we get to enjoy it.

MBC: Are they turned on by dancing with anonymity?

EC: One of my most common requests now is guys wanting to be filmed so they can read other people’s comments about their cock.

MBC: Do you think they are masturbating over it later?

EC: I hope so!

MBC: Are solitary masturbation orgasms different to orgasms experienced with another person?

EC: I think so. You’re sharing your energy with someone. When you have sex with someone else, you suddenly get access to this emotional world that a lot of people don’t get to access. That’s one of the things I really love about sex. Only after we have sex do we have these special conversations. People are so much more vulnerable and trusting. Sex is one of the most vulnerable things you can ever do. Through hook-up culture, you’re being absolutely vulnerable to someone you’ve never met before. It’s almost submission. A lot of these men, outside of the glory hole, I don’t think I’d ever talk to them. In real life, there’d be no situation where we’d be talking to each other. People like coming to the hole because it’s an escape, it’s this playground where we can just have fun and talk and fulfil any fantasy.

MBC: Your work is transgressive. It’s not part of the norm of most people’s lives. I always wonder, is your art about the relation to norms or the act of sex itself. If we were all doing what you do, would you still do what you do?

EC: When I was young, I was fascinated about the things that make people feel scared. That was the start of my relationship with sex. Once, I was playing with my cousin, and my stepdad, who was always drunk, told us to go upstairs and not to come down. Kids being kids, we didn’t listen, so we went back down, sneakily, into the living room, and in there, I saw the first porn I’d ever seen, a point-of-view—this guy was fucking this girl at the beach on a chaise-lounge. We were so fascinated by what we saw, and we started giggling, and I remember my stepdad’s face when he looked at us. I’ve never seen that in a face. It was disgust. It was turned on. It was shameful. It was anger. How was this suddenly drawing so much emotion? That really started my love for sex. I wanted to understand it.

MBC: I’ve never watched your porn. I would, but probably not for gratification. I’m not anti porn though.

EC: I didn’t think you were. I didn’t think you were the type.

MBC: (Laughs) I’m not. And neither are you.

EC: Not at all. I love looking at different studios, genres, actors, sets.

MBC: Do you watch hetero porn?

EC: I watch hetero porn ninety-nine percent of the time. The energy’s so different and I get turned on a lot by seeing a man passionately eating a woman out. I really love this idea of making someone feel good.

MBC: Have you ever been in love with a woman?

EC: Yeah.

MBC: Is that part of your life anymore?

EC: Oh, another thing. This happened to me when I was twelve—I got my girlfriend pregnant. We didn’t keep it. Thankfully. She was thirteen. She was my girlfriend at that time. I was part of that naughty bad boys’ group in high school. I had attractions to men that I knew were there. But this was my way of becoming the alpha in the group, by basically being the first one to fuck my girlfriend. I was also really horny. I was making out with all the girls all the time. At the time I was also quite religious. I remember praying to the Lord that I would never have sex with a woman again if I didn’t have a child.

MBC: Are you a typically alpha male?

EC: No.

MBC: It sounds like you knew how to be one.

EC: I tried. But it felt like a costume. It felt like a drag. I was desperate to be accepted in that group. To be protected. They were real troublemakers. I wasn’t. I was just the smart kid in class who just tried to be a bad boy.

MBC: More than tried.

EC: Okay, I was a bad boy. I was sneaking out at lunchtime. Drinking in the cemetery. Fucking my girlfriend in the cemetery. I was pretty naughty.

MBC: Do you ever watch lesbian porn?

EC: No. I just really love cock.

MBC: And the best cock is in hetero porn?

EC: Aesthetically. The power to it. The angles.

MBC: Has porn changed lately?

EC: It’s become braver. Genres that were considered taboo are more normal. There’s more gangbangs and creampies now, as an example.

MBC: Is that a good thing?

EC: For me it is. I love it. Or, even with gay porn, back then there was a lot of condom use because of the fear of HIV. But now because of PrEP, we’re able to have less distinction between gay porn and straight porn.

MBC: It’s just porn. It’s just sex.

EC: Natural sex, they call it. There’s even high-definition intimate romantic porn. All 4K. This guy asked me for that.

MBC: Your clients get you to put on porn?

EC: If they want to. Normally it’s just of me sucking some guy’s cock through the glory hole. The best-of-the-best performances. It’s a bit meta.

MBC: What angle do they see the porn from? Isn’t there a wall between you, where the glory hole is?

EC: It plays on their side. And there’s two cameras, one on each side of the wall—one facing me, one shooting their back.

MBC: The best-of-the-best only shows you?

EC: It’s me servicing a cock to the best of my abilities.

MBC: So, they see your face on the video, but it’s point-of-view, like the point of view of the wall.

EC: The ones who are more comfortable, I capture their back.

MBC: Got it. They’re watching you servicing someone else, from another session, from the eyes of the wall. And there’s a camera on their back. And a camera on you. That’s interesting. How did you come up with all that?

EC: I create porn that turns me on. I watch my own porn to gratify myself. That’s always my rule when doing something. I need to get off on it. I need to benefit from it. I’m doing this for me. Have you ever made amateur porn?

MBC: No. Or professional. Sometimes you use quite gritty language. Like, instead of saying my butt or anus you’ll say…

EC: My bussy?

MBC: Yeah. Or words like cumguzzling. This hyperbolic language that’s quite animalistic. What is that language?

EC: It’s recognising I’m still in the porn realm. There’s an erotic, pornographic element to my world, so I’m drawing from within that context. Some of it is comedic. With the way I label the guys who visit, I try to be unfiltered. Sometimes I even try to be problematic. That’s the nature of porn searches. You almost have to be a bit problematic to find what you want.

MBC: This is not a vitamin store.

EC: No. You want, ‘Big white cock fucking Asian pussy, hairy, blah blah blah, creampie’. You’re just yelling at it. Give me this.

MBC: I have a safe question. Is there anything good about conservative values that you’re going against?

EC: Depends what those conservative values are.

MBC: You sometimes highlight clients who are married and visit in secret. There’s a sense of scandal and betrayal, and I’m not saying the responsibility lies with you at all. But are you just doing your work and they’re the client? What are you trying to show?

EC: Through what I document, I want to show the reality of modern sex. And part of it is that. In a day, five of the seven clients have girlfriends or are married. With my work, my goal is to be as close to truth as possible.

MBC: A truth you’re creating?

EC: I’m creating the truth, but I’m also reflecting it.

Der Greif x Quantum Reshaping The Future of Photography

By To Be Team

Artists in Conversation: Gabriel Cole and Brendan Huntley

By Rachel Weinberg

Atong Atem – A Familiar Face on a New Horizon

By Sophie Prince

Joshua Gordon's Latest Transformation

By Annabel Blue

GARETH MCCONNELL on MASKS, TRANSFORMATION and COMMUNICATION

By Annabel Blue

Jason Phu on Latest Exhibition 'Analects of Kung Phu' at ACMI

By Alexia Petsinis